Zero distances are sort of like favorite automobiles and preferred EDC handguns: There are many choices and if we do our own part, most of them will get the job done. Nonetheless, the question of the “best” range at which to zero a particular rifle comes my way fairly often. I have traditionally been a 100-yard-zero guy, but more out of habit than for ballistic reasons. I know my holds at all practical distances with the rifles I shoot when zeroed this way, so it is comfortable and easy. Even so, my zeroes are not etched in stone, and over the past couple of years, I have slowly changed my ways to better reflect the cartridges I use and how I use them.

Two key factors have the greatest effect on the optimal-zero distance for a rifle: The external ballistics of the projectile chosen, and the way it is used. For example, a traditional 220-grain, .30-caliber round-nose, jacketed softpoint is going to plow through the air a lot differently than a svelte 143-grain, .264-caliber Hornady ELD-M bullet. Likewise, they were designed for very different purposes, so the best zero for each round is going to be determined by these factors.

Generally speaking, the slower moving, less aerodynamic the projectile and the farther away the target aimed at, the greater the angle between LOS and LOB.

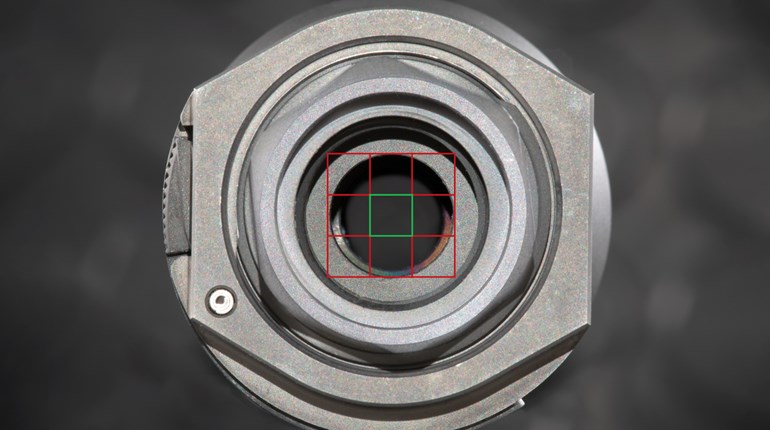

A rifle’s line-of-sight (LOS) and line-of-bore (LOB) form an angle as they extend from shooter to target. Think of LOS as a laser line that extends from your eye through the optic (or sights) to the target. Conversely, LOB angles upward to some degree due to the fact that as soon a bullet leaves the muzzle, gravity begins pulling it downward. The point(s) at which LOS and LOB (well, technically the bullet trajectory) intersect is the zero distance. Generally speaking, the slower moving, less aerodynamic the projectile and the farther away the target aimed at, the greater the angle between LOS and LOB.

Short, slow, stubby bullets will quickly pass upward through LOS on their way to a distant target—like a ball lobbed hard and high into the air to gain distance. The bullet will come back down through the LOS at a farther distance as gravity has its way. This second intersection is typically used as the primary-zero distance. With fast-flying, aerodynamic bullets, the LOS/LOB angle is much smaller. This moves the first bullet/LOS intersection farther downrange and reduces the bullet’s deviation above and below LOS. Tweaking the primary-zero distance allows moving the secondary-zero distance (SZD) to a useful spot along a bullet’s pathway.

When I covered the popular 50/200-yard zero in 2010, I used 62-grain, 5.56 NATO M855 ammunition to compare zeros at various distances. The AR platform’s newfound popularity was still in its early days, and many shooters were using this green-tip, surplus load for the first time. That comparison demonstrated the utility of 50- and 200-yard zeros out to 300 yards when using an average 16-inch barrel’s muzzle velocity. The beauty of such a setup is that elevation compensations (over and under intended points-of-impact) are minimized out to practical distances. But is the 50/200 zero a one-size-fits-all tool? Not quite, but it is still a good starting point for many rifle and cartridge combinations.

In order to compare different zeros with several common cartridges, I referenced JBM Ballistics’ Trajectory-Simplified calculator that can be found at jbmballistics.com. JBM’s tool allows a much wider variety of data inputs and provides greater detail outputs than most of the ballistic apps in our phones and wind meters. It is also free to use, so long as you have internet connectivity. Using the calculator, I analyzed bullet rise and drop (respective to LOS) out to 500 yards, with zeros at 25, 50, 100 and 200 yards.

My goal was to see if the 50/200 zero could be equally useful for other common rifle loads. The comparison produced a lot of data—too much to be useful here. The condensed results in this table show each cartridge’s SZD using a 200-yard primary zero. Regardless of cartridge, this zero yielded less deviation above or below the LOS (out to 500 yards) than all other zeroes checked.

A secondary benefit to determining a close-range SZD is that if you do not have access to a full-size rifle range, you can adjust your sights to the closer distance. Using the examples in the table, zeroing at 25 or 50 yards (depending on the cartridge) will still get you very close at 200 yards. These are just a few examples. So long as you input the correct muzzle velocity, sight height, bullet data and atmospheric info, you can play with any good ballistic program to find the optimal distances for your cartridge.

Remember to factor in how you plan to use it. Long-range shooters will likely find very different sweet spots than short-range hunters and home defenders. Always confirm the data provided by ballistic programs and chronographs/radars by shooting your gun-and-cartridge combinations at multiple distances.

A hazard of keeping my head over a shop bench or behind a riflescope most days is that I am not fully up to date on trendiest tricks and techniques. If you have a better zero system that already works, such as the Triple Bravo Adenoid zero or the Dropkick-Niner-Niner-Scratchy zero, by all means, continue to use it. The tool that helps you shoot more effectively is the best one to use.