Whether combat or competition when it comes to shooting performance, how fast is too fast? How fast is too slow? How fast is just right? The rhetorical question is “What is it that you are you shooting for?” Is it for a job qualification? National level competition? Everyday carry (EDC) for protection or survival? Keeping it real for each reason why, there are four recommended guidelines to dial your speed shooting skills up to the speed of life.

Guideline 1. Going fast has nothing to do with going fast

Believe it or not speed shooting is not about “going fast.” Rather, it’s about being so efficient with your physical mechanics that there is no wasted motion. No extra movement, no adjustments, no micro-corrections or even an extraneous thought.

As pedantic as it may sound, the first step to doing anything proficiently is to be able to do it without time or accuracy requirements. As an example, can you clear your cover garment, access your handgun and present the muzzle to the target with no timer and in dry fire only. If you can do that, then can you set a time for example 2 seconds and make that time in dry fire?

Once you can accomplish that task under that time constraint you can then go to the range and introduce another layer of complexity atop of your presentation skills. That added layer can be an accuracy requirement.

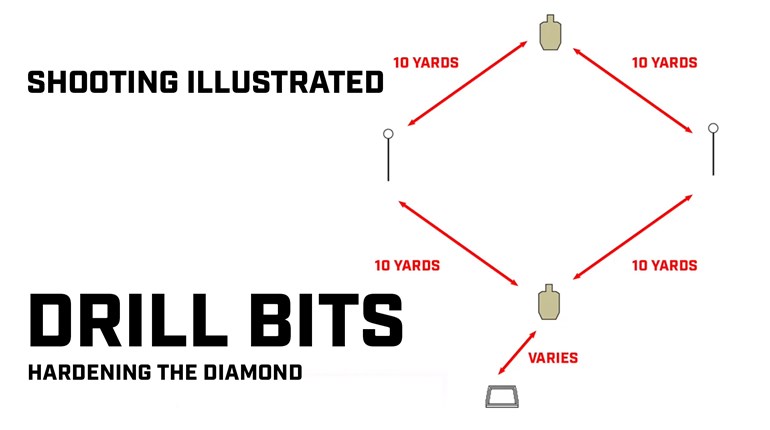

Select an easily attainable goal, say a target set at the ten-yard line. Set your accuracy requirement to make “A-box” hits (an upper-thoracic, combat-effective round-placement target area) at the ten-yard line. Once you can do that from the holster with no time, then add your two second requirement.

By isolating each specific gun handling and marksmanship skill you iron out any unnecessary movement such as over travel or under travel. The less extraneous movement, the more efficient, which equates to the appearance of speed.

Guideline 2. Repeatability supersedes catching lightning in a bottle

Now that you have removed as much unnecessary movement as possible and have found a pace at which you can accomplish that, the next step is to be able to do it more than one time in a row.

The next question is “Can you do it and then can you do it again?” If it is repeatable then the magic number is five. One time is a good first try, second time could be luck, third could be chance, fourth could be you’re having a good day, but the fifth time you do it, well, now that’s straight up skill. If you can pull it off five times in a row then, there’s a pretty good chance you’ve got the skill down well enough that you can repeat it on demand.

Once you have attained repeatability, now is the time you can change your performance requirements. Making the task more difficult to perform pushes you up to the next skill level. Reduce your time requirement down by a half-second (or so) or change target difficulty.

Time cuts should be made in small increments say between a tenth and a quarter second. You want to keep pushing yourself until one of your wheels falls off. If you’re not pushing time, then you can’t get a wheel to fall off. Once a wheel falls off (bad grip, bad hold, change in grip pressure, bad press, et al) it will tell you what and where you need the work to attain that next level.

Target difficulty can change by placing the target at a greater distance, making the strike zone smaller, raising the penalty for failure and the like. Increasing target difficulty will also cause a wheel to fall off, which is how you learn to overcome that next level obstacle. If you’re not making mistakes in training, it’s impossible to increase your performance.

A novice can catch lightning in a bottle once in a while, whereas the professional cannot do it wrong.

Guideline 3. Be consistent being consistent

On-demand performance for a master-level competitive shooter is that they can do it 80 to 85 percent of the time on demand applying national level requirement standards.

The secret to being consistent is to be consistent. Get your consistency down so pat that it’s like breathing to you. Find your way points (specific stop points in time and space along the way), get consistent with getting to those way points. If you become consistent hitting your waypoints on demand then your overall technique will be consistent. Unwavering and default consistency in execution presents the appearance of speed.

Guideline 4. Set your performance standards

When setting those specific performance requirements, what are the “recommended standards” and how does that match up with the speed of life?

Any law enforcement officer that I have ever interviewed over the decades who has been involved in an officer involved shooting (OIS) said that he “did in the street like he did in training” and when monitored (usually by onboard video replay) were times between .32 and .45 second splits (time measurement between multiple shots on the same target) at about seven yards or less.

Gleaned from similar interviews with U.S. Department of Defense tier one government assets (T1Gs) over the decades they pretty much said the same thing that “split times can vary anywhere in the .30s (three tenths of a second split time at 7 yards and in) is good enough to get the job done.” If good enough to get the job done for a T1G then good enough to get the job done for me.

One of the most common speed of life questions posed these days is the ubiquitous sub-second draw form concealment - is it absolutely necessary?

To be frank, what’s the downside to having that skill?

However, playing devil’s advocate, if you train for a sub-second draw and you default down to 1.35 to first shot every time even when you’re not having an “on” day (which is more often than not!) again where’s the downside to that?

“On” days are only about 25 percent of the time – if you train regularly. You should plan on the likelihood of an “off” day. On any off day you will revert to your default performance which happens to be your speed of life.