A barrel’s twist rate is only one factor in determining how a particular load will perform in a rifle.

I read your recent article “Handgun Rifling: Bullet Weights & Barrel Twists." I have a few points I would like to question or discuss; no problems with the article, just some other things I find interesting to consider. I will begin with an idea that I have been thinking about regarding short-barreled rifles and AR pistols used for defensive purposes. My thoughts concern bullet rpm, or revolutions per minute, imparted on a bullet by the twist rate of the barrel as it exits the muzzle, and also a component of its velocity. I have questions about some things: Will all bullets hold together at this rpm due to centrifugal forces? Will the jacket on the bullet deform or separate at this rpm?

Consider that the velocity plays a role in this rpm as well and decreasing a charge will reduce this rpm or increasing a charge will also increase this rpm. Maybe bullet manufacturers would consider specifying their maximum rpm per bullet type, and what minimum and maximum rpm generally destabilizes it or causes it to disintegrate? Maybe another consideration is, can a bullet tolerate this rpm for 1 second, but fail afterward?

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think this would be an interesting topic to be covered and would love to hear your thoughts on the subject.

Perry Malin

Leesburg, TX

There has been much study and commentary on twist rates regarding how they affect the flight of a bullet in handguns, rifles and other single-projectile launchers. Similarly, there are some guidelines with which to work on this subject, but there are many variables to these guidelines that have to be considered, as well—too many to discuss in the space available. I can, however, cover a few to answer the majority of your interests.

You are correct: Twist rate and velocity have a major impact on the stability, accuracy and flight integrity of a bullet, but, consider the following. The design of the bullet, for example, will dictate the rpm it will withstand when it is fired. Some bullets have thin jackets designed to disrupt quickly on impact such as those designed for hunting varmints. Match bullets, in order to maximize weight in a certain-size envelope, may also have thin jackets because lead is heavier than copper. The stress on the jacket material when fired in deep-grooved or rough barrels with sharp-edged lands is enough to weaken the jacket to the point of separation soon after it leaves the barrel in some cases. Once the core loses the support of the jacket, it also disintegrates due to the centrifugal forces imparted by the rpm of the bullet, often resulting in a small cloud of dust between the muzzle and the target. This usually happens within the first 50 yards of flight, which is just milliseconds out of the muzzle. I have yet to see a bullet hold together for a second or more and then come apart in flight. I suppose it could happen, but it is unlikely in my opinion.

Generally speaking, it would be difficult to drive a bullet fast enough to the point of disintegration out of a short-barreled rifle or AR pistol in the calibers these firearms are typically chambered in, even with a tight twist rate. Usually the culprit of bullet disintegration in these guns is related to the bore or an attached muzzle device. I have seen this to be the case when the muzzle device was not attached in perfect alignment with the bore, causing a disruption in the bullet as it exited the muzzle.

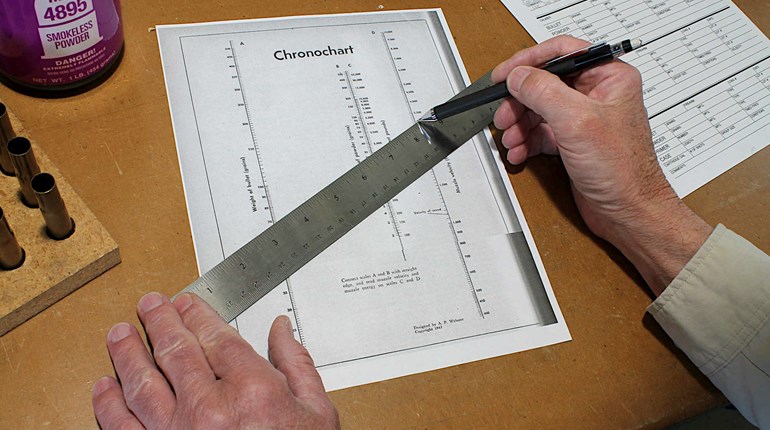

Bullet manufacturers often recommend twist rates for bullet stability on the containers they are sold in, particularly in the heavy range for a given caliber, assuming they are shot at velocities commensurate with their intended purpose. Often, they will advise (if contacted by the customer) an rpm range for optimum stability and integrity for a particular bullet. Using the formula of known muzzle velocity multiplied by 720, then divided by the measured twist rate in inches, will determine what characteristics the bullet should possess for optimum performance in any gun—providing the barrel is in good shape and the bullet isn’t damaged in the feeding and chambering process or by a muzzle attachment.

Keep in mind that ballistics is not an exact science. There are guidelines and so-called rules to go by, but there are many exceptions that have to be considered. The best way to achieve success is to stay within the recommended guidelines offered by the industry and experts regarding bullets and their capabilities. There is certainly nothing wrong with experimenting outside of the box as long as safety is not compromised. You won’t know what works in your guns and what doesn’t unless you give it a try.