I’ve spent a lifetime studying the frontier West, specifically the histories and gun handling of Western lawmen, gunfighters and outlaws. In those days, with no formal firearm training, folks had to learn on their own; on-the-job training, if you will. Certainly, when any distance was involved, the shootist used his or her pistol sights or at least looked over the top of the gun to orient it with the intended target. However, when the encounter was up close and personal, they just poked their gun out at the threat using one hand, and sent lead downrange. We have come to call that point shooting.

With the coming of the 20th century, point shooting continued in popularity among serious students of the gun. William Fairbairn taught his Shanghai police to point shoot with revolvers and semi-autos. Soon after, notable people like Rex Applegate, Charles Askins, Jr., D.A. “Jelly” Bryce, Dan Combs, Bill Jordan and many others advocated and taught point shooting when the threat was at close range.

Somewhere along the line, many of these shooters began to incorporate a crouch into this defensive technique. One argument was that one will naturally crouch anyway when the guns start going off, so they might as well incorporate it into his or her practice. Others suggested that crouching made one a smaller target. FBI Agent Jelly Bryce took it to the extreme and got down almost to the ground when making his draw. Bill Jordan, on the other hand, chose to stand erect and moved only his shoulder, arm and gun hand when point shooting, as did Frank Hamer. When I went through the police academy in the late 1960s, our FBI firearm instructor was still teaching point shooting—with a crouch—for close-range work.

Sometime after World War II, Jeff Cooper and associates began to experiment with defensive-shooting techniques that came to be called The Modern Technique of the Pistol. This involved standing erect, using two hands on the gun and using the sights to deliver the shots. The first serious defensive-handgun competition also resulted from this new technique. More importantly, data from actual gunfights seemed to indicate that a person was more likely to get first-shot hits on the threat and was likely to stop the attack quicker with this method. People with limited time to train and limited ammo budgets found they could more easily develop an effective skill level using the Modern Technique. Point shooting, as a result, began to fade in popularity and, for some, became associated with trick and exhibition shooting. Many of today’s defensive shooters have absolutely no experience with point shooting at all.

For the most part, I agree with the idea that the Modern Technique is the better way to go. However, I would suggest that there is absolutely nothing wrong with developing skills in both disciplines. As we know, the most dangerous attacks are those when the criminal is virtually in our face. Yes, I know we all preach awareness, but that doesn’t always happen, now does it? We may get caught when we are not paying attention to our surroundings like we should. Or, our attacker may have some prior experience at this business and knows how to slip in close before making their move. It doesn’t really matter what the reason is; you’ve got a dangerous crook in your face. Do something—and do it right now—while you still can.

This is the sort of situation where point shooting has value. When the crook is within 6 feet of you, with some sort of weapon already in his hand, you may not have time to make the draw, take a two-hand hold and look at your front sight. You’ll be lucky to just get your gun out and get a shot or two off.

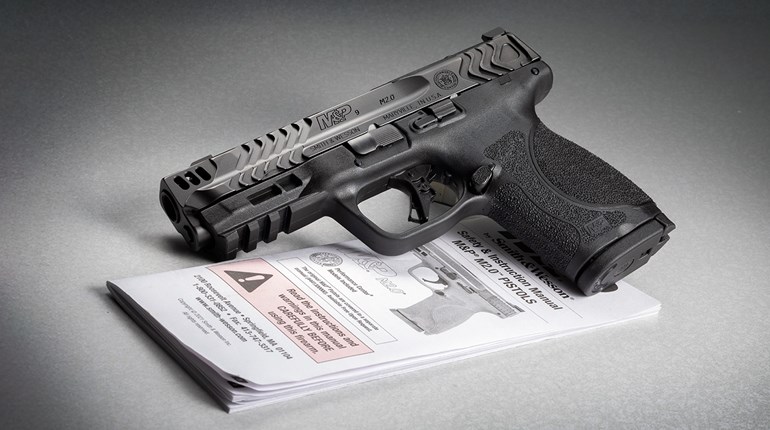

But, like any other shooting discipline, point shooting must be practiced to be effective. You need to know at what distance you can keep all shots in the vital zone of the target—not just once in a while, but on demand. And, you need to avoid switching carry guns, because the feel and weight of different guns can affect the hit potential.

The only time that shooting from the hip is a good idea is when the threat is so close, we can’t raise the gun any further. We want to practice punching the gun toward the target while we focus our eyes on the exact spot on the target that we want our bullets to hit. But, we should always remember that in close-range encounters, it is possible that the attacker might be able to grab our gun or knock it out of the way.

So, my suggestion would be that the new shooter first gets training in the Modern Technique of the Pistol, learning effective marksmanship and the ability to hit a target precisely and quickly. And, the majority of subsequent practice should be in that mode. But, at the end of a session, set up a target, move in closely and work on developing your point-shooting skills. Who knows? It might just be the thing that ultimately saves your life.