Well, OK, we don’t actually know that the “Big Guy” Himself was carrying an M1911 around on His hip while He was tending the garden there in Eden, in case of snakes, but the devoted fanboys of John Moses Browning’s most famous pistol sure do seem to imply it sometimes. (“Why was his middle name Moses? Because he was beloved by God,” as the joke goes.)

At any rate, after two world wars and several smaller dustups, the Colt M1911-pattern pistol had achieved an otherwise unassailable prominence in the American pistol pantheon. It was the choice of government toters from the armed forces to the Texas Rangers, and handgun sports from Bullseye to the various action-pistol disciplines had rule books written to keep 1911s sequestered in their own divisions and away from lesser pistols.

It was from the second of those disciplines, action-pistol shooting—and specifically IPSC (International Practical Shooting Confederation)—games where today’s story starts.

The stages of fire in an IPSC match are kinda freeform. It’s a game of problem-solving with a pistol in your hand. With Open Division pistols, it didn’t take long for people to seek mechanical advantages to give them an edge. Among the first were extended magazines that protruded from the bottom of a 1911’s grip, bumping up capacity to 10+1 rounds of .45 ACP.

The next jump came in 1985 when Canadians Ted Szabo and Thanos Polyzos founded Para-Ordnance, initially selling frame kits that would let the owner of a 1911 pistol plop their existing top end—slide, barrel, sights, recoil assembly, and all—onto a frame that held a double-column magazine with a capacity of 14 rounds of .45 ACP. It wasn’t long before they were selling complete pistols, which were called (as you can probably guess) the Para-Ordnance P14-45.

While the Paras used novel countersunk grip panels, allowing them to be only fractionally wider than the 1911 single stacks from which they sprang, the realities of the double-column .45 ACP magazine meant that the total circumference of the grip was noticeably greater, with chonky, square corners and a broad, flat frontstrap.

The next step in larger capacity 1911-type pistols came when pistolsmith Virgil Tripp, already well known for raceguns and specialized racegun parts, brought engineer Sandy Strayer on board, and the two took an idea for a double-stack 1911-based design Tripp had been working on and brought it to fruition.

The result was the modular STI 2011, patented in 1994. It differed from previous offerings in that the frame rails and dustcover formed a metal chassis, which held the lockwork, and then the grip, magazine well and trigger guard were a separate polymer unit pinned to this frame, which allowed the grip diameter to stay manage- able. It was a big hit on the gamer circuit, but first Strayer left and then Tripp sold the company to pursue other projects.

STI the company was still there, though, and needed to grow market share beyond the very insular world of IPSC/USPSA shooters. The problem was that the original STI 2011 pistols had a reputation, like many high-strung gamer guns, of being finicky and specifically needing magazines tuned to the gun. Since they had started out using a single magazine-well dimension for every chambering from 9 mm up to 10 mm and .45 ACP, this was understandable.

Rebranding as Staccato, it went after reliability issues with a vengeance. In its quest for acceptance by LE agencies and tactical teams, the company pursued consistency in magazine manufacture and, as it was the early 2020s, non-9 mm chamberings became less and less of a priority. It finally got to a point a couple years back where it released a new pistol, the Staccato CS, that used an entirely new magazine tube.

While the geometry of previous Staccato magazine bodies could be traced back to the 2011s of the early 1990s and the need to accommodate larger cartridges for action-pistol sports, the new 3.5-inch-barreled Staccato CS used a magazine with a completely different geometry. Rather than a weird, multi-stepped design that owed a lot to the old Para-Ordnance mags of the 1990s that accommodated .45 ACP and 10 mm, the new CS mag resembled the modern Browning Hi Power/Beretta 92/Smith & Wesson Model 59 magazine that was explicitly designed around the seemingly ubiquitous 9 mm round.

The CS was a success for Staccato, but a 3.5-inch-barreled pistol isn’t playing to its core market, and thus came the next pistol to use the new magazine geometry—and the subject of this test—the Staccato C.

“But Tamara!” you say, “there already was a Staccato C!” Well, I am not wise in the ways of the marketing gurus, but apparently the existing single-stack Staccato C wasn’t selling in big enough numbers to keep it from being discontinued and its name reassigned to a new and hotly anticipated double-stack 4-inch pistol.

That 4-inch number is the key measurement here. This is a pistol that sits right in the center of the sweet spot that’s been occupied for decades by blasters as varied as the Smith & Wesson Model 5906, the SIG Sauer P229 and the Glock G19. A pistol with a 4-inch barrel and 15- to 17-round magazine is the ideal “do everything” size. Can it be a duty gun? Sure. Can it be used by detectives and plainclothes cops? Of course. Can a private citizen use it for concealed carry? With a modicum of effort and careful holster selection, you betcha.

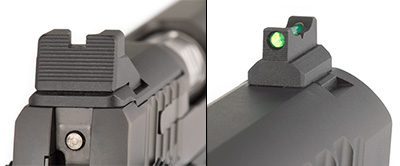

Up on top, the new Staccato C gives clues to its roots in the custom 1911 world. The flattop milled along the sighting surface of the slide is flanked by a broad bevel on either side, in the classic “tri-top” look. Up front is a dovetail-mounted front sight, tall and narrow, matte black enhanced with an eye-catching, bright-green fiber-optic light-pipe insert. It’s matched to a robust, ser-rated, flat-black rear with a wide notch for fast sight acquisition and a bluff front to enable one-handed charging by snagging the rear sight against a belt, holster mouth or boot heel. The rear sight is actually part of the cover for the red-dot mounting system, which we’ll circle back to.

The slide features broad, angled grasping grooves, three pairs up by the muzzle end and four more aft of the ejection port. Said ejection port is lowered and flared for reliable ejection (mangling the case mouth on spent brass is less of a worry on a 9 mm 2011 than a .45 ACP one, the original reason for flared ejection ports).

The alloy frame has a full-length dustcover with an accessory rail sporting a single Picatinny-type notch. While you could use a compact light like a TLR-7, it’d look weird. This blaster is meant for a SureFire X300/Streamlight TLR-1-style full-size WML. There’s a single-side slide stop and magazine release, both suitably low-profile, and ambidextrous thumb safeties of the slim, extended variety referred to as “tactical” in 1911-speak.

The trigger is curved but with flat-surfaced, skeletal, polycarbonate shoe pinned to a titanium bow, a descendant of that original Tripp-designed STI trigger which, I must confess, I’ve preferred and used on my own custom 1911 builds for 20 years now. Take-up was minimal, overtravel was negligible, and it broke crisply and consistently at 4 pounds.

The polymer grip module incorporates coarse-textured panels molded in fore and aft and on both sides, as well as a pronounced mag funnel. It can be had in compact (15-round) or full-size (17-round) lengths. Our test gun was 15-round length. Have you held a Glock G19? About like that.

The Staccato C uses a bushingless, partially fluted bull barrel, but thanks to the 4-inch length, it uses a reverse recoil-spring plug, which means it can be field-stripped without tools. Simply clear the pistol, partially retract the slide to line up the takedown notch, push out the slide stop, and run the slide assembly forward off the frame. Then, flip the slide over, carefully extract the recoil-spring assembly to the rear, followed by the reverse recoil-spring plug. Rotate the barrel link over center until it’s in the fully forward position and draw the barrel out the front of the slide. Reassembly is, as one would assume, in the reverse order.

The $2,599 question here, then, is “How well does it work?”

At the time of this writing, I’m halfway through a 2,000-round test and I am still waiting for the first malfunction of any type to occur. After the first 200 rounds with no malfunctions using the iron sights, a Trijicon RMR HD red-dot sight was mounted via a factory mounting plate. The factory mounting plates include a built-in backup iron sight (BUIS) and are secured by a single screw. Theoretically, these mounting units are pretty much of the return-to-zero variety, but you’ll likely want to use some thread-locking compound and witness marks to avoid having to unexpectedly find out for yourself.

The Staccato C is one of those pistols that causes a conundrum. It’s definitely premium priced, but it also delivers premium performance. Reliability is outstanding and accuracy is phenomenal, aided by a stellar trigger. On the other hand, magazines and holsters aren’t going to be available at Greasy Joe’s Dixie Bar & Grill & Part-Time Gun Store out in the middle of nowhere. An aftermarket will develop, but it will always be smaller than that for less exclusive pistols.

It’s very much a Pareto-Principle pistol: You can get almost as good for less dough, but if you want a super-premium, 4-inch, 15-round, 9 mm carry pistol without compromises, Staccato will happily hook you up with one.