Back in the day, I recall some chatter about issuing short-barreled .44 Mag. revolvers to police officers. This was prior to the massive acceptance of 9 mm ammunition as the dominant defensive-handgun round worldwide. I personally know one rural cop who actually carried a .44 Mag. on duty, but I’m unaware of any department that officially adopted the big magnum cartridge. Only one agency (San Antonio PD, I believe) briefly went with the slightly less powerful and newer .41 Mag. In this age of greater-capacity, lightweight, polymer-frame semi-automatic pistols loaded with the latest high-performance 9 mm ammunition, it might be a bad idea to suggest revisiting the .44 Mag. as a good choice for defensive use. However, I’ve been rather impressed shooting a 4-inch Colt Anaconda recently, so let’s do it. But first, let’s take a look at the gun.

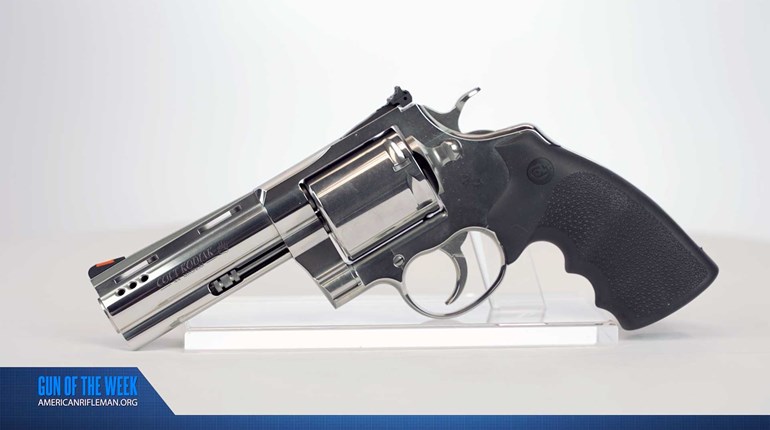

The new Anaconda is a large-frame, stainless steel, .44 Mag. double-action revolver that can be fired either single- or double-action. The ventilated rib proudly claims its lineage to the original Python revolvers. The Anaconda incorporates a full-length ejector-rod shroud that protects the ejector rod from being bent out of line during normal use. It also adds weight up front near the muzzle to help control recoil, thus reducing recovery time between shots. Historically this was less important given the .44 Mag.’s perceived role as a hunting handgun, but it’s a critical feature in a hostile encounter with a two-legged adversary or a large four-legged critter that has decided to charge.

The Anaconda’s muzzle has a recessed crown to prevent damage to the rifling. The stainless steel frame and barrel are highly polished on all external surfaces, including the hammer and trigger. The topstrap is drilled and tapped for a scope (or other optic.) While this was once considered non-essential in a tactical application, it has taken on new meaning due to the massive increase in the use of red-dot optics on defensive handguns.

Front and rear sights are blued (black, if you prefer) in the tradition of iron sights—no colors or white outlines anywhere. This all-black arrangement is my preference when shooting outdoors in adequate lighting, and in fact, was more than adequate when accuracy testing at an indoor range. Should you prefer some color for faster acquisition of the front-sight blade under reduced light conditions, you can change front blades by removing a single lock screw at the muzzle. The rear-sight blade is dovetail-mounted into the sight base with windage settings locked in place by a setscrew. Elevation adjustments are controlled by one vertical screw located just in front of the rear-sight blade.

The Anaconda features Hogue rubber grips that slide on from the base of the grip and are secured by a screw in the bottom of the frame. The rubber grip doesn’t enclose the Anaconda’s backstrap, which reduces the distance from the back of the gun to the trigger: a real boon for shooters with small hands trying to run a powerful double-action revolver. Surfaces on the grips appear to be more of a stippling treatment as opposed to the impressed checkering style. The grip panels are rather narrow, and the finger groves are quite pronounced and slightly longer than some other grips I’ve used. The Hogue grips fit my hand pretty well and make the rather bulky 4-inch Anaconda much easier for me to control whether firing single or double action.

The Anaconda’s extra .2 inch of cylinder length (compared to my Smith & Wesson Model 29) allows the use of extra-long/heavy bullets. That extra .2 inch of steel in the cylinder also adds weight to help tame the recoil of whatever loads you care to shoot. And for the record, the Anaconda’s slightly larger diameter cylinder still accepts the same HKS speedloaders used by the N-frame Smith & Wessons.

Anacondas now use the same type “V” spring design as the new Pythons. According to my Lyman trigger gauge, average double-action pull weight for the Anaconda is 9.5 pounds and 6.25 pounds when firing single action. Note trigger-pull measurements were made after firing around 200 rounds combined of .44 Mag. and .44 Spl. ammo without any cleaning of the gun. That’s still a very smooth trigger, but probably capable of lighter pull weights when the gun is clean. There is a slight rotational play in the cylinder when the hammer is either at rest or fully cocked. This is the same characteristic exhibited by the “V” spring Pythons, but on both Anacondas and Pythons, the cylinders lock tightly in place when the trigger is pulled all the way to the rear and the hammer falls. The 4-inch Anaconda’s cylinder has no play at the time of cartridge ignition regardless of whether the shooter fires single or double action.

All guns have trigger stack, because they’re starting with zero applied pressure and increasing it until the trigger moves. The issue is how far the trigger must move to fire the gun, and whether the shooter has to noticeably adjust their pressure somewhere during its travel. Single-action triggers typically move a tiny fraction of an inch and require between 3 to 5 pounds of pressure to drop the hammer. A double-action revolver trigger has to move something like half an inch to first cycle the action, then push the transfer bar up until it covers the firing pin and finally release the hammer. That’s a lot of work for a trigger finger accustomed to a Single Action Army or Model 1911. The Anaconda’s trigger moves quite smoothly with a steady, consistent increase in pressure until the gun is almost ready to fire. For the most precise shots, the shooter can briefly hesitate to verify sight picture before applying the last bit of pressure to fire. This is called “staging,” and not all double-action revolvers allow for it.

So, have I made a case for officers abandoning their Glocks and doub-ling the weight of their handgun by purchasing a Colt Anaconda? I think not, particularly when you consider all the gear and gadgets cops have to carry these days. But, what about folks who spend time in the more open spaces of America? Two things occurred to me while testing the Anaconda that made me consider revisiting its possible use as a carry gun. First was the fact that in one range session with the 4-inch-barreled Anaconda, in excess of 100 rounds of full-power .44 Mag. loads were fired, something I haven’t been able or willing to do for about two decades. Yes, my signature looked a bit strange when I signed off the range, but both hands were pretty much fully functional. To me, that says the additional capabilities of a fully loaded .44 Mag. are available to, and manageable by, most folks who might need them. Second, there’s a great variety of .44 Spl. ammunition available from standard weight lead bullets to lighter weight/lower recoiling jacketed hollowpoints designed to expand significantly. Maybe this won’t convince anyone to trade in their 9 mm for a magnum revolver, but it can remind folks that the .44 Mag.’s capabilities are available to those who believe they might be needed.