When looking through an optic, the reticle is the dot, crosshair, hashmark, triangle, circle or geometric shape in the field-of-view. Used properly, it allows gun owners to deliver accurate shots downrange. It’s a simple principle, but the arrival of red-dot optics has changed the landscape dramatically.

Today there are so many options it’s hard to find agreement on which one is best. As Joe Fruechtel, SIG Sauer’s director of Optics Product Development, explained, “We always joke that if you ask 10 people their opinion on reticles, you will get 20 different answers.”

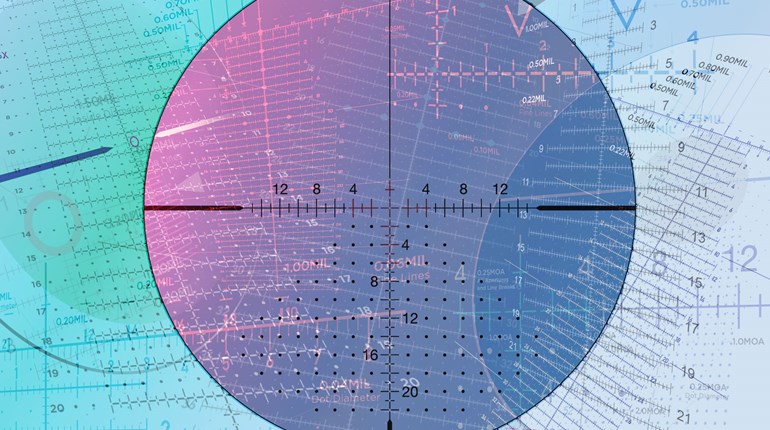

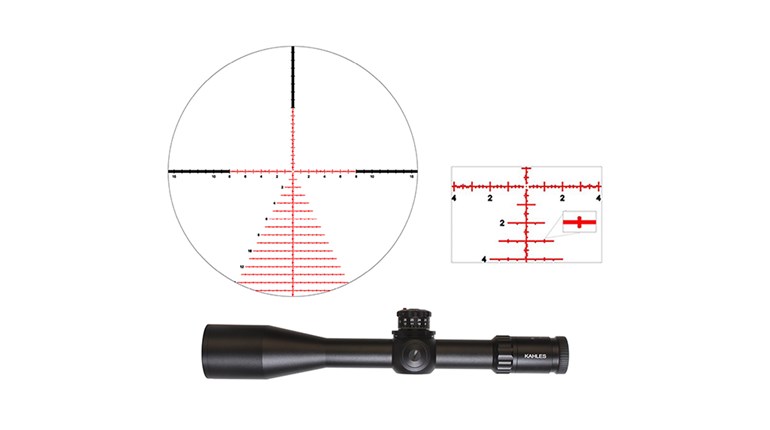

Traditional riflescope reticles today are either wires sandwiched between lenses or etched glass in the scope. When mounted in front of the magnification lens, they are first-focal-plane optics. When behind that lens, they are second-focal-plane models. Springs anchor reticle assemblies in place. Adjusting the elevation or windage knobs increases or releases their pressure, moving the crosshair. It’s a clever system sometimes plagued by binding in early models—a rare malady today.

Red-dot sight technology advances so fast that a one-size-fits-all description is risky. Most often, though, an unseen LED in the housing—directed up and at the glass shooters look through—illuminates. The reflection that travels to the enthusiast’s eye is the reticle.

Windage and elevation are usually adjusted by screwdriver or Allen wrench and, unlike riflescopes, you’re not always stuck with one reticle. The Meprolight Foresight, a Bluetooth-connected “red dot,” offers a 20-reticle selection, for example. Steiner’s DRS1X comes with three user-selectable versions on board—two of them allowing rough distance estimation.

Most red-dots are 1X, making them ideal for both-eyes-open work up close—personal protection. That asset magnifies when their reticle occupies more real estate in the field-of-view. Steiner’s MRS Micro Reflex Sight, for example, has a 3.3-MOA red dot for fast, potentially lifesaving target acquisition with a pistol. Many traditional riflescopes have sub-MOA-sized lines intersecting at the crosshair, which is great for precision, but can be tough to quickly acquire under stress. At Burris, “The 3-MOA dot has been our most successful red-dot size,” according to the company’s director of Marketing, Jordan Egli.

The approach is similar at SIG Sauer. As Fruechtel explained, “The smaller dots allow for more precision at farther distances, while the larger dots are typically quicker for shooters to spot and aim with.”

The Leupold DeltaPoint Micro red dot has a 3-MOA diameter and the firm’s DeltaPoint Pro version is 2.5 MOA. Dots are 1-MOA size in the firm’s RDS line for rifles.

Manufacturers have created a cutting-edge blend of technology to create an all-new generation of red dots that are rugged, reliable and even bring many virtues once reserved for long-range riflescopes to pistols.