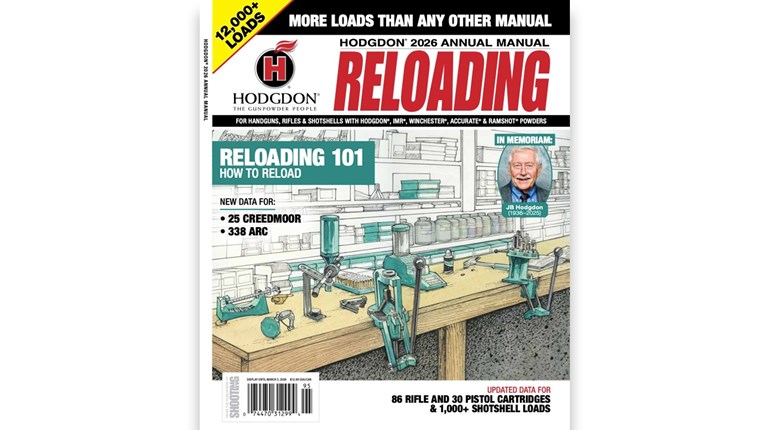

A view into a Dillon Precision XL650 progressive reloading press midway through loading some .300 Blackout with 180-grain Rainier Ballistics FP bullets.

The .300 Blackout has had a few years to grow now. Early on, the claimed goal was to have ammunition prices on par with the inexpensive .223 Rem. and 5.56 NATO loads. We were even close for a short time. However, nowadays, inexpensive, big-name mass-produced .300 Blackout is harder to find. If you want cheap, you’re looking at having to buy remanufactured ammunition, which can sometimes be of questionable quality. Another option is to load your own. To reload your own .300 Blackout, there are some must-have tools needed to make high-quality handloads.

Before you embark on this, assuming you haven’t already, you should probably find a reloading manual and get familiar with the process of reloading your own ammunition as well as finding the load data you’re going to need. There are a handful of solid reloading manuals out there from Speer, Hornady, Sierra, and Barnes, to name a few. For specific loads, there is also information available on Hodgdon Powder’s website.

One thing you may want to decide before reloading .300 Blackout is whether you want to load subsonic ammunition, supersonic ammunition or both. The subsonic will be quieter through a silencer, while the supersonic will obviously carry more energy for tasks such as hunting.

Of course, you need a reloading press. If you’re only feeding a bolt-action rifle or only slow-firing an AR-15, then a single-stage press, such an RCBS Rock Chucker, will work. If you need greater amounts of ammo, you may want to look at a turret or progressive press. I’ve seen somewhat large quantities of ammo loaded on a single stage, but it is time-consuming and sometimes involves bribing children to do things like checking it all in a case gauge (be sure to check your state’s child labor laws). Turret- and progressive-loading press options exist from Hornady, Lee Precision and Dillon. I use a Dillon Precision XL650 and I’ve been happy with it.

Once you have your press, you’re going to need appropriate dies. Dillon’s dies for their machines can be pricey, but the company also generally uses a carbide sizing die. As far as the other machines, I would stick to what they recommend.

One of two tools I find indispensible, not including those for making necessary die and press adjustments is a case gauge. The case gauge is to be used to check every loaded piece of ammunition. I know some may say to check every fifth, or tenth, or whatever number cartridge. I check every single one for the sake of making sure there won’t be any problems during my shooting sessions. I’d urge you to do the same.

The second of the two tools I find indispensible is a good set of calipers. My preference is the dial version, as they don’t require batteries and also probably because I’ve been using them on and off for most of my adult life. Digital calipers are typically cheaper than equivalent-quality dial calipers. At this point, I will say, I’m not a fan of plastic calipers, as the material involved is just too prone to damage, and I’ve always been skeptical of their accuracy. Be sure to store them away from anyone you think may try to use them in place of a crescent wrench. In fact hide all tools you value from such people.

At some point in the .300-Blackout reloading process, you’re going to need to be able to weigh your powder charges. For this, you will need a powder scale. I generally use a balance-beam version, as it’s less expensive, but if you’re inclined to spend more money, you can opt for a digital. I’d probably use one if I had one.

As far as powder goes, you’ll need to find something appropriate for the loads you’re intending to make. This could be Hodgdon H110, Hodgdon CFE Black, Accurate 1680, Reloder 7 or a variety of others. You have a number of options. Again, if you’re using .300 Blackout ammo in a gas-operated, semi-automatic rifle, you’ll have less flexibility in powder, since the gun needs enough gas to cycle reliably. Where 180-grain subsonics are concerned, so far I’ve had good luck with Reloder 7. Heavier subsonics can use Hodgdon CFE Black, Winchester 296 and Accurate 1680. For lightweight supersonic loads IMR 4227, Hodgdon CFE Black, Hodgdon H110, Winchester 296 and Alliant 2400 are good options. As I’m sure you noticed, some powders handle a fairly wide variety of bullet weights.

Bullets for the .300 Blackout are where things can also get interesting. There are offerings from Sierra with one of the notables being their 220-grain MatchKing. This one seems to reign as a favorite, but it isn’t cheap. Nosler also has a heavyweight offering, in addition to various lighter weight options. Rainier Ballistics has introduced plated 180-grain bullets for subsonic use only. They are a lot more economical for plinking than spending the money on the Sierras. The Rainier Ballistics bullets come in a “wedge” or a hollowpoint offering. Other companies, such as Hornady, also have a variety of projectiles available ranging from light to heavy weight for the caliber. The typical range of bullet weights runs from about 110 grains all the way to 240 grains.

For brass, you have some options. You can purchase factory-new brass made by Hornady or Remington. There are also companies converting once fired 5.56 NATO brass (usually with the LC head stamp for Lake City) to .300 Blackout brass. This I usually get from GI Brass Locker, though there are other sources out there.

Primers will be whatever is prescribed in the load data that you obtain. I don’t recommend deviating from this for safety reasons. Most data I have seen specifies small-rifle magnum primers.

At some point, you may want to know how fast your .300 Blackout bullets are actually going. This is particularly helpful when loading subsonic ammunition as you can make sure your bullet speeds are still below supersonic velocities but as close as to those velocities as you can get.

If you choose to load subsonic ammo for an AR-15, some bullet ogives can interfere with first rib in the standard AR magazine, causing the ammo to bind and not feed correctly. Some people have chosen to load their ammo shorter to remedy this. However, that can be problematic, as the shorter length can also make it easy for a loaded .300 Blackout cartridge to be chambered in a .223 Rem. or 5.56 NATO chamber. Caution is warranted here. A better solution to this problem is to use the .300 Blackout-specific magazines made by D&H Tactical and Magpul.

A couple nice-to-have items that are not necessarily required for reloading .300 blackout are a brass tumbler and brass separator. If you are planning to reuse your brass, and you should, you will probably want to clean it. The cleaner your brass is, the longer your dies will last, especially if that brass has been in the dirt at all. To clean your brass, you need a vibratory polisher/tumbler, polishing media and brass separator. Corncob media is fine for most brass. If you are using heavily soiled range-pickup brass, you’ll need the more aggressive walnut-hull media.

All in all, you’ll have some upfront costs but if you shoot a lot of .300 Blackout, you’ll find the break even point in short order. It isn’t hard to save yourself roughly a third of the cost of a box if you’re used to buying quality ammunition. Once you reuse your brass, your ammunition costs will decrease even more. You'll either spend less or shoot more. Take your pick. Either way, I think we can all agree both are good.