The phrase "Ready, Aim, Fire" has become synonymous with the act of discharging a firearm. This sequence of actions has been used for centuries and has played a crucial role in the evolution of firearm performance shooting. The phrase encapsulates a disciplined approach to shooting that maximizes accuracy, precision, and safety.

Firearms date back to the 14th century, with early hand cannons and matchlock muskets. These early firearms required significant time to reload, which influenced early battle tactics. Soldiers often formed lines, delivering volleys of fire at close range, with commanders calling for "Ready, Present, Fire" as a means of coordination.

As firearms technology advanced, military leaders recognized the importance of proper training. The phrase "Ready, Aim, Fire" emerged as a standardized drill during training exercises, instilling discipline and uniformity among soldiers. Proper handling, aiming and firing became essential for the effective use of firearms.

The evolution of firearms and military tactics brought about changes in the "Ready, Aim, Fire" sequence. As breech-loading and repeating firearms became prevalent in the 19th century, the emphasis shifted towards individual marksmanship. Soldiers were trained to take careful aim before firing, a crucial development that would influence the rise of competitive shooting in the civilian world.

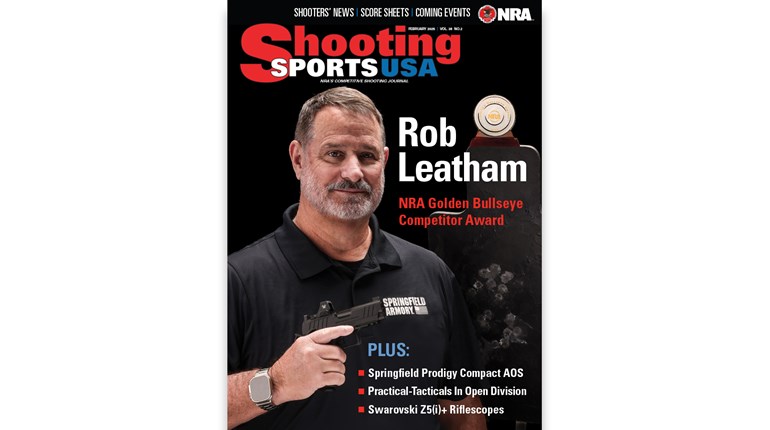

Modern firearms performance shooting revolves around marksmanship principles that build upon the foundations laid by military training. In the mid-1980’s through the 1990’s performance shooting pioneer Rob Leatham further refined this military adage of into the shooting process of “bring stability to alignment and break the shot without disturbing that alignment.”

How did Leatham derive “Stability, Alignment, Break” form “Ready, Aim, Fire?” The answer is what defines the contemporary art and science of performance shooting.

Ready

When the commanders of old issued the command “Ready!” based on the weapon system of the time, that one word command might encompass a multi-step process that took a considerable amount of time in comparison to our modern standards.

In the 16th century, muskets and pistols were matchlock firearms, which required several steps to be ready for firing. The process of readying a musket involved various preparations and precise actions.

The first step was to load the musket with gunpowder. A soldier or musketeer would measure the correct amount of black powder using a powder flask or horn. The powder charge was typically poured into the musket's open muzzle.

After adding the powder, a small piece of cloth or paper (the wadding) was inserted into the muzzle to hold the powder charge firmly in place. The wadding served to create a better seal and prevent the powder from spilling out during the next steps.

The next step was to load the lead projectile (a musket ball or bullet) into the musket. The soldier would use a ramrod, typically attached under the barrel, to push the projectile down the barrel until it sat on top of the powder charge. Matchlock muskets had a small pan located near the lock mechanism, which was used to hold a small quantity of fine gunpowder known as "priming powder." The pan was covered by a hinged or sliding metal plate. The soldier would open the pan cover and carefully pour a small amount of priming powder into it.

A matchcord, also called a match, was a length of slow-burning cord made from twisted fibers, often treated with saltpeter to maintain a steady burn.

One end of the matchcord was attached to the serpentine, a curved metal arm that held a piece of smoldering match material. With the musket now loaded and primed, the soldier would shoulder the weapon and bring it to a firing position. The matchcord was kept away from the priming pan to prevent an accidental discharge.

Today the word “Ready” translates to stabilizing the gun. If it’s a shoulder mounted gun, then that would be made to brace against the body creating optimal stabilization with the muzzle facing downrange in the direction of the target. Hence Leatham’s term ‘stability.’

Aim

Throughout the era of non-percussion firearms, it was necessary to maintain stability and prevent any ignition of the powder in the flash pan prior to when you had established confirmation of alignment.

Given the advent of primers and enclosed casing ignition we no longer have the concern of loose powder, but we do share the same challenge of maintaining stability during the alignment process during which we are aiming the gun. The idea being to have the gun stabilized with a functional grip and body brace so that the muzzle falls within the margins of an acceptable arc of wobble when aligned with the target.

Fire

To fire a 16th century musket, the soldier would slowly bring the burning end of the match cord toward the priming pan, igniting the priming powder. The ignited powder would then travel through a small touchhole in the barrel, igniting the main powder charge and propelling the projectile down the barrel towards the target.

It's important to note that loading and firing a musket in this manner required training and practice. Musketeers had to be proficient in these actions to maintain a disciplined rate of fire during battles. Matchlock muskets were eventually replaced by more advanced flintlock and then percussion-cap firearms, which simplified the firing process and improved reliability.

In our modern era of optimal reliability, we are still tasked with high performance fire control. Today it is the shooting process where you stabilize the gun (ready), acquire muzzle alignment with the target maintaining an acceptable arc of wobble (aim), and of course break the shot with a steady and precise trigger press without altering stability or alignment (fire).