The iconic, but misunderstood, .30 Carbine cartridge is criminally overlooked when it comes to a pistol-caliber long gun for home defense.

The story behind the M1 Carbine is fascinating. And, while this column is about ammunition, it’s impossible to discuss the “carbine cartridge” without some gun history. In 1940, the U.S. Army was looking for a light rifle or carbine. Initial work on the rifle that would become the M1 Carbine was started by Jonathan “Ed” Browning, the brother of none other than the famous firearm designer, John Browning. After his death, Winchester hired David “Carbine” Williams, who had begun work on a short-stroke, gas-piston design while he was—of all things—serving a sentence at a North Carolina minimum-security work farm. The resulting rifle would serve with American military personnel in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

The cartridge for the M1 Carbine was for the most part a rimless version of the .32 Win. cartridge introduced in 1905. The standard load was a 110-grain FMJ bullet with a muzzle velocity of about 1,900 fps when fired from the M1 Carbine’s 18-inch barrel. One interesting aspect of the .30 Carbine cartridge was that it constituted the first major use of non-corrosive primers in a military firearm.

Jeff Cooper, founder of the American Pistol Institute (API; now known as Gunsite Academy) and the man who introduced the general-purpose Scout rifle concept, was not a fan of the M1 Carbine or the cartridge. In a 1966 article, he wrote that the M1 was, “… an attempt to replace the pistol for military personnel who could not pack a rifle and who could not hit with a pistol. I think it must be considered that this was a mistake.” There’s no doubt the ballistics of the .30 Carbine cartridge placed it between a pistol and a real rifle like the M1 Garand or Cooper’s Scout rifle. However, while it might not have had a revered place on the battlefield, when operations became close, such as when clearing towns or cities, the carbine’s size and close-range power were appreciated.

I spoke to my father at length about his time in Korea. While fighting there, he served in a variety of positions including squad leader, designated marksman and machine gunner. When I asked him which firearm he most liked to carry, he said it was the M1 Carbine. But, he added that when it came time to fight, he wanted the BAR. Given the type of battlefield conflicts he (mostly) took part in, this made sense; the BAR had more reach and power. Today, our Army is outfitted with a rifle chambered for a cartridge—the 5.56 NATO—that does a good job of fulfilling the role of a close-quarters carbine and a battle rifle. However, for civilians wanting a home-defense carbine offering more power than a handgun and one that is easier to shoot more accurately, the .30 Carbine cartridge in a nimble, compact, long gun makes sense.

This is partly why carbines chambered for 9 mm have become very popular. While they’re easier to shoot more accurately than a pistol, out of a carbine the best performing 9 mm loads—something like the 124-grain Speer Gold Dot—will only generate a muzzle velocity of about 1,400 fps and produce only about 540 ft.-lbs. of energy. By comparison, Hornady’s Critical Defense .30 Carbine load will leave a carbine’s muzzle at about 2,000 fps, generating almost 1,000 ft.-lbs. of energy. Not only is the .30 Carbine more powerful, with expanding bullets like the Hornady FTX you can expect around 20 inches of penetration with expansion approaching a half inch.

For civilians wanting a home-defense carbine offering more power than a handgun and one that is easier to shoot more accurately, the .30 Carbine cartridge in a nimble, compact, long gun makes sense.

Of course, the appeal of the .30 Carbine cartridge is somewhat diminished by the available firearms chambered for it. You can still find original M1 Carbines and modern-manufactured clones do exist, but reliability is quite magazine-dependent, and most don’t have that modern, tactical look. Ruger offers a Blackhawk chambered for the .30 Carbine, but it’s hardly the ideal defensive handgun. For a time, AMT offered the large, .30 Carbine version of its semi-automatic pistol, and then there’s the rare and somewhat odd Detroit, MI-made Kimball pistol. With an overall cartridge length of 1.68 inches and operating pressure of 40,000 psi, the .30 Carbine was not optimally configured for a pistol.

This, of course, is another reason a carbine chambered for the .30 Carbine has lost favor with modern shooters. With 9 mm carbines from Beretta, Kel-Tec, Ruger and others that use pistol magazines, they allow you to share magazines between your carbine and your pistol. Though this magazine-sharing feature is cool, I’m not sure it outweighs the ballistic advantage offered by the .30 Carbine, which is essentially twice that of the 9 mm when fired from a rifle with a 16- to 18-inch barrel.

Though a revolver cartridge, the modern .327 Fed. Mag. cartridge is ballistically quite similar to the .30 Carbine. It fires a .312-inch-diameter bullet as opposed to a .308-inch-diameter bullet and operates at 45,000 psi as opposed to 40,000. The .327 Fed. Mag. cartridge is also about .2-inch shorter. Out of a 5-inch barrel, a 100-grain bullet will have a muzzle velocity of around 1,400 fps and when fired from an 18-inch barrel, it will produce a muzzle velocity of approximately about 2,000 fps.

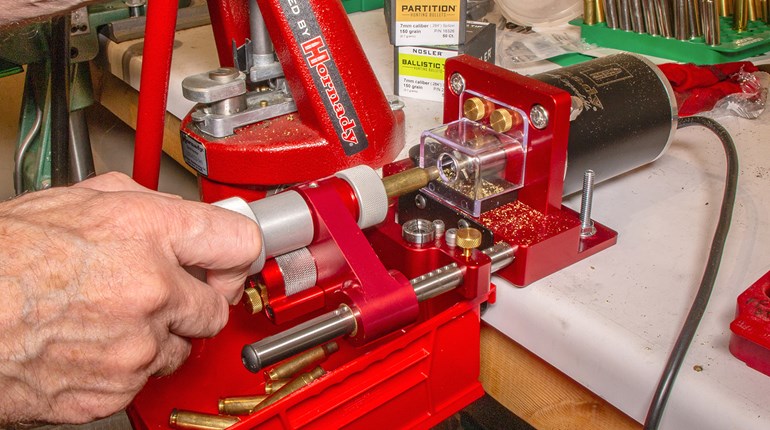

Several manufacturers offer loads for .30 Carbine suitable for self-defense or home protection, and Buffalo Bore even offers a 125-grain hardcast load at 2,100 fps with 1,224 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy. Maybe it’s time you gave the .30 Carbine some consideration. But beware, original M1 Carbines can be expensive. However, a new M1 Carbine from Auto Ordnance retails for about $1,100, which is similar to new offerings from Inland Manufacturing, as well.

Or maybe it’s time ammunition/firearm manufacturers looked at introducing a new cartridge that’s similar to the .30 Carbine. One that will offer .30 Carbine-like performance from a carbine-length barrel, but that will also be pistol-compatible and offer magazine interchangeability. With the advancements we’ve made in ammunition since 1940, this should not be all that complicated.