Aftermarket triggers abound for popular models of handguns, but sometimes they may require professional fitting owing to slight variations in manufacturing methods and processes.

My experience comes from the U.S. military and as the department armorer and primary firearms instructor for a municipal law enforcement agency. In all my years dealing with service pistols, including mil-spec 1911s, Beretta M9s, Glocks and SIG Sauer P220s, if a part broke, we simply replaced it with a new part, no fitting required, then test fired and reissued the gun back into service. Part interchangeability was a given in our service pistols, rifles and even our shotguns. With the advancement of manufacturing capabilities and tolerances, one would think that a specific gun type or model could be assembled out of parts from the manufacturer (or aftermarket) for that would function reliably and accurately.

I found this situation not to be the case when I attempted to assemble a clone of a Gen3 Glock G19 out of parts advertised as being compatible with that model from multiple manufacturers.

What started out as a fun project became one of frustration, because the parts that supposedly would work and function together did not.

Was I sold a bill of goods, or is this perhaps typical of “modern manufacturing” today?

John, via e-mail

There are several factors to be considered given your experiences in the military, on the police force and as a hobbyist working with guns for enjoyment.

Service firearms in the military branches of the United States have long been required to have part interchangeability. This requirement came as part of the contract awarded to the manufacturer and, in some cases, delved into such detail as to specific materials and manufacturing processes.

The primary idea was a matter of ease of maintenance and logistics to keep the firearm operational at the lower echelons of users for greater periods of time. If a small part broke or was lost, the gun could be put back in service by installing a new one or by scavenging a part from a firearm not in service. No doubt economics had a role to play in it as well.

With the transition from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols in the law enforcement community during the late 1980s and early 1990s, there came recommended-maintenance schedules, which included springs and a few small parts, as well as a periodic detailed disassembly for cleaning, inspection and lubrication to maintain peak operational readiness. Part interchangeability became an attractive feature, as it minimized maintenance costs and the time to get a gun back in service when it broke or needed scheduled maintenance. This was particularly important since the vast majority of the guns in law enforcement are in constant service, and often spare guns were not available.

As firearm patents expire, entrepreneurs capitalize on producing replacement parts and even whole guns replicating an existing name-brand model at a lesser price or possessing some desirable differentiating features. Classic examples of this phenomenon are the Colt M1911, Glock G19 or the ArmaLite AR-15 in their seemingly infinite varieties from multiple manufacturers.

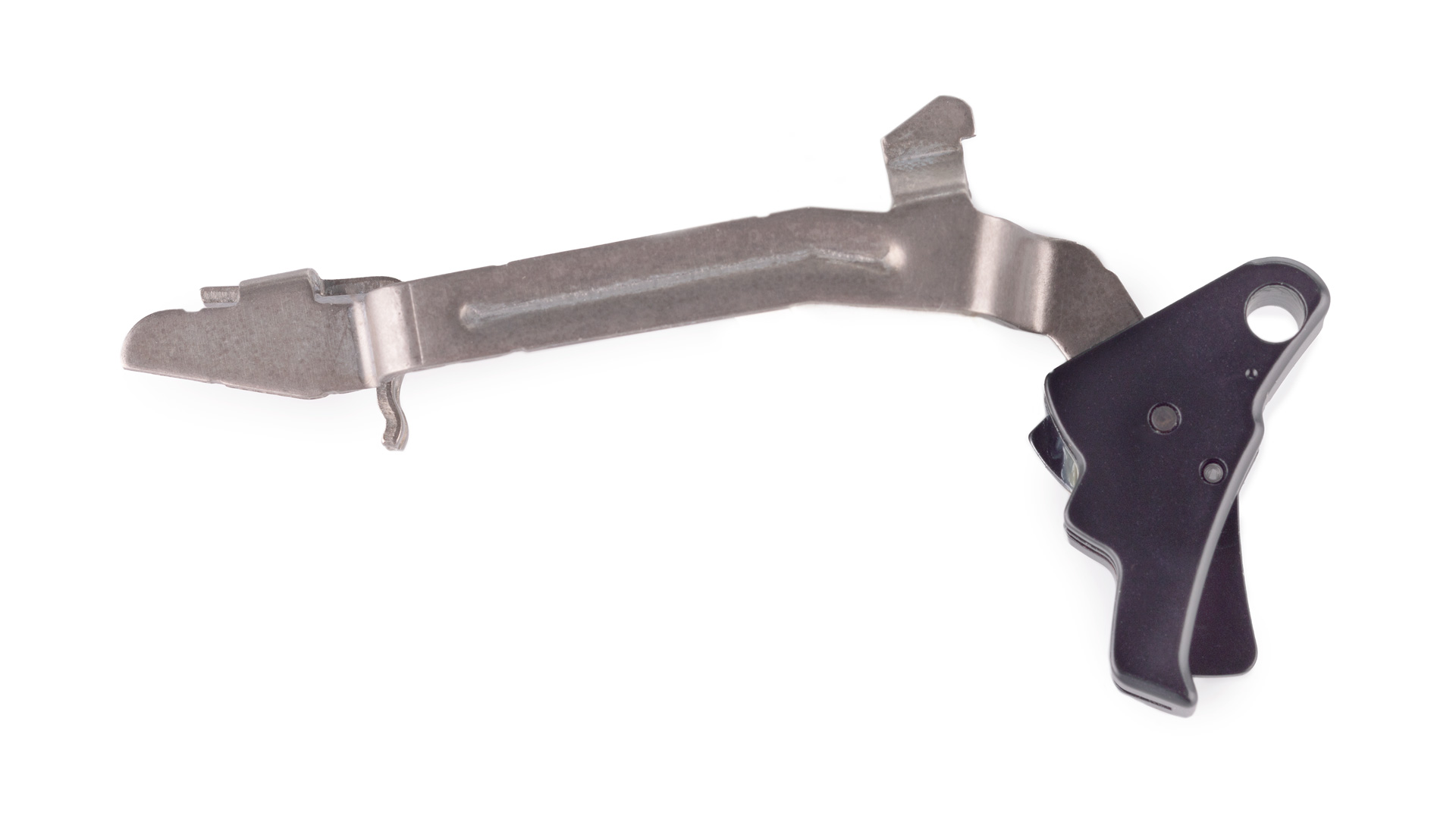

Often, the parts are reverse-engineered from existing ones found in original guns, because the original technical-data packages containing the original specifications for the guns or parts are not readily available or have been corrupted somewhere along the line and are not 100-percent accurate. As a result, this introduces variables and tolerance differences into the production process that exceed part compatibility with one another—especially if parts from multiple aftermarket manufacturers are used to complete one gun. That is not to say the parts are defective, but in some cases the stack-up of tolerances may exceed the functional reliability of a firearm. Trigger and safety mechanisms are particularly affected because of the close tolerances necessary for them to work effectively.

A good practice for the hobbyist building parts guns or modifying existing guns with aftermarket parts is to stick with one brand of parts in the areas where critical fit and tight tolerances are necessary for proper function. A general guideline is the smaller the part or assembly, the closer the tolerance requirements for proper function.

With all of the potential variables in play in assembling a gun from multiple parts sources, it is important to prove functional reliability of the end product before dependability on the level of the original model replicated can be considered.