While we don’t recommend actually duct-taping your head to a stock, keeping your shooting form intact without interruption during a course-of-fire is integral to accurate shooting.

At some point in our early shooting lives, most of us were told to “follow-through” by placing our sights back on target immediately after firing each shot. If you failed to develop the habit properly, that advice was probably followed by regular reminders, admonishments and—if a drill sergeant was involved—the occasional boot to some portion of your prone body. In later life, many of us repeat this guidance (minus the boot) when teaching new firearm enthusiasts, though the “why” behind follow-through isn’t always fully explained.

The most common reason given for getting back on target is practical in nature. Regardless of whether one is faced with a situation that requires the use of deadly force, confronted by a dangerous animal or hunting to fill the larder, it’s a bad idea to assume one shot will automatically have the desired effect. Immediately bringing one’s sights back onto target allows for rapid and accurate follow-up shots, if needed. This is good advice and sound practice. However, as golfers, baseball players and anyone else who uses a tool to rapidly, forcefully and accurately move a “projectile” to a desired spot knows, follow-through is also a critical component of accuracy.

As curious shooters who strive to improve our skills, it’s natural to want to know whether or not our intended points-of-impact (POI) have been hit after we hear and feel our shots break. With non-reactive targets, that requires us to either lift our heads to check close targets, or to look through spotting scopes, binoculars or the same riflescopes used for distant shots. Unfortunately, this desire can develop into a habit that prevents us from hitting the things we’re aiming at.

I can hear the ballisticians’ protests right about now, and they’re correct on one point: Follow-through takes place long after a bullet has left the bore. This is fairly easy to demonstrate through numbers. Don’t worry, no mathematicians were harmed by the knuckle-dragger math that follows, though my math major/software engineer son cleaned it up for me.

According to the National Institutes for Health, the average eye blink takes about .4 second. Using a 175-grain Sierra Match King .30-caliber projectile with a muzzle velocity of 2,500 fps as an example, we can deduce that it will travel 1,000 feet in the same .4 second that it takes to blink. While the exact rate of acceleration inside the barrel is governed by many internal ballistic factors, some sources indicate that it reaches the speed of sound in the first 2 inches of rifling. If we use a conservative 1,775 fps, which splits the speed of sound (at standard atmospherics) and the 2,500 fps at the muzzle, it would take approximately 11 ten-thousandths of a second (.0011) for our bullet to exit a 24-inch barrel. That’s approximately 364 times faster than the average eye blink.

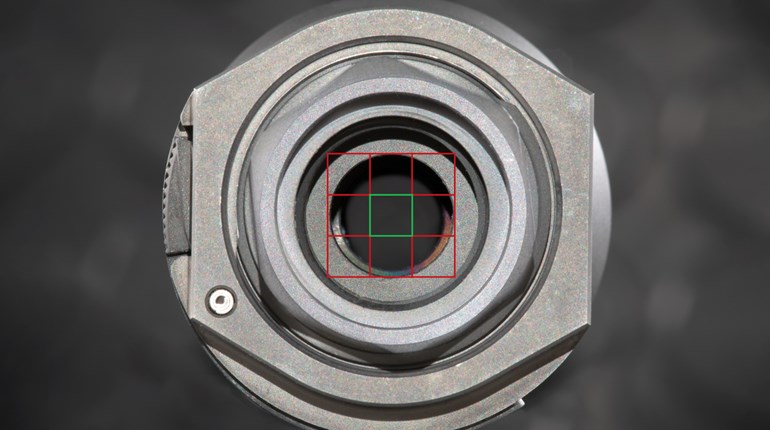

Thus, it’s safe to say that if one’s body and rifle are stable at the instant that a primer is ignited, one cannot possibly move the rifle faster than the time it takes for the bullet to exit the barrel. The problem is, that’s not our problem. Moving the rifle before the bullet starts its trek through the bore is the part of accurate shooting that follow-through actually deals with. Once a shooter succumbs to the desire to check their work immediately upon firing, the habit of “lifting” the firing eye off of the sights is soon to follow. Because this problem is normally progressive, the shooter typically begins to lift off of their sights (or optic) before firing. Those micro movements of body and rifle yield pulled shots and frustration. Normally imperceptible to the shooter, lifting can be detected by an observer who watches closely from the side or over the firing shoulder.

Apart from duct-taping your head to the rifle’s stock, the only way I know of to counter this problem is to force yourself to follow-through after each shot by consciously bringing your sights back onto your point-of-aim. It does not matter that your bullet is long gone. It does matter that by forcing yourself to follow-through back to the point-of-aim, it’s possible to break the cycle of prematurely looking for your impacts. Once you’re back on target, you can come off the gun, check your last shot, take a nap, whatever.

A third benefit of good follow-through habits is a sort of hybrid of the first two and limited to specific scenarios. In modern military sniping, it’s common for small teams to be spread extremely thin while covering a large area. As a result, having a dedicated spotter is often a luxury. Effective follow-through is required by snipers who must observe their shot impacts through their own riflescopes. Done correctly and at distances beyond about 200 yards/meters, “self-spotting” allows a sniper’s reticle to be placed back on the point-of-aim before bullet impact. This permits confirmation of a hit or immediate preparation for a follow-up shot. If it’s a miss—and the impact is observable—most modern sniping reticles enable very rapid corrections. During the post-Sept. 11 portion of my time as an active-duty sniper, my teammates and I self-spotted approximately 90 percent of the time, and to good effect. Likewise, rifle shooters who hunt or train over extended distances and master follow-through can self-spot when no one is around to glass over their shoulders.

Techniques for ensuring follow-through during the firing cycle vary. Mine is to get my reticle (or sights) aligned with my intended POI and then devote about half of my conscious brain to maintaining that image. What’s left of my brain takes any “slack” or first stage out of my trigger, controls my breathing cycle and silently screams at me to follow-through as I break the shot. When I do this, and assuming my body position is solid, I shoot well and my sights come right back on target. On the occasions that I mess this up, it’s always a result of poor concentration.

If you haven’t been a good follower in your own rifle shooting, give it a try and see if it helps tighten things up downrange. If not, at least you’ll be ready for follow-up shots (and you won’t look like a prairie dog).