Sometimes, writing a magazine column is like time travel. I’m writing this just as the first frost of autumn is in the forecast, a few days away. It’s time for me to start thinking about rotating the cotton socks to the back of the drawer and the wool ones to the front, and folding the short-sleeved T-shirts away and bringing the long-sleeved ones out of storage. The lightweight, airy concealment garments of summer are getting put on hangers in the basement, and the oversize flannel ones moved into the hall closet.

By the time you read this, it will have already been cold for a month or two, depending on your location, and you’ll be counting down until days start getting noticeably longer and pitchers and catchers report to spring training.

For the people of my tribe—the Toting Americans—if you live in the parts of the country where it gets good and cold in the wintertime, you’ll likely have already made the adjustments to your carrying habits necessitated by the realities of climate and weather. For some people, wintertime carry means going to a heavier caliber for their primary carry piece. Noted firearms trainer Massad Ayoob is a fan of the .45 ACP for wintertime use in cold climates on the theory that even if one’s assailant is wearing heavy clothing that clogs the projectile’s hollow-point cavity and prevents expansion, you still have a .451-inch projectile doing the work.

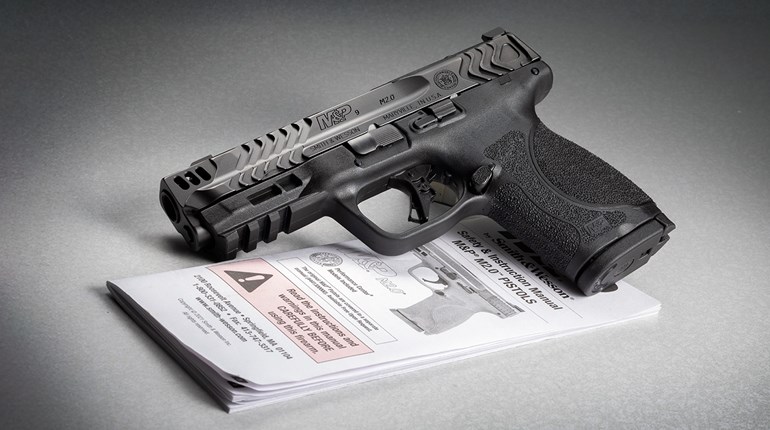

While this is less of a worry with modern, “barrier-blind” projectiles (and it’s debatable how much difference that extra .1-inch of projectile diameter makes assuming identical shot placement) it’s undeniable that some folks do feel better about an extra-big bullet when an assailant may be wearing clothes with more layers than a fancy wedding cake. My head knows my 9 mm Glock G17 is going to work as well, all things being equal, as my .45 GAP Glock G37 against heavy clothing, but my heart doesn’t always believe it—and my head doesn’t always win the argument.

There are also people of my acquaintance who may not change calibers, but do switch to heavier projectiles for the cold months to ensure adequate penetration. For instance, switching from 115-grain or 124-grain 9 mm loads to 147-grain for heavy-coat season. If you do this, make sure to re-zero your dot sight or adjustable irons if possible, and if not possible at least confirm the difference in point-of-impact relative to your warm-weather loads out to 20 or 25 yards.

Relatedly, if your normal load is something like Hornady Critical Defense, which is designed for delivering moderate recoil and defeating light clothing while still expanding reliably, the winter months might be a time to consider switching to Hornady’s Critical Duty, which is a more barrier-blind projectile and deals with heavy clothing and intermediate barriers with more aplomb.

Another effect that winter weather may have on concealed carry is how one carries one’s primary firearm. In pleasant summer weather, an AIWB holster under an untucked polo shirt or a deeper concealment rig like a PHLster Enigma under a tucked-in T-shirt is only a yank of the cover garment away from a blisteringly fast presentation with a modicum of practice. Colder temperatures, though, may mean additional layers. Sweaters, fleece vests, light jackets, etc. can interfere with that practiced presentation. In light of this, some people may switch to a strong-side holster, perhaps outside of the waistband, for the frigid months.

Let me say up front that I’m not the world’s biggest fan of shoulder holsters for a couple of reasons. The first one is that it’s hard to find places that will let you practice live fire from the leather with one on. The other reason is that the drawstroke involves reaching horizontally across your chest, which massively telegraphs the draw and gives an opponent inside a double wingspan’s distance a splendid chance to step in close and tie up your gun hand by pinning it against your chest. Those disadvantages may be outweighed, especially in winter, by ease of concealment if you’re going to be wearing a cover garment all the time. Of course, you’re then stuck with your cover garment if you go inside someplace warm. You’ll have to evaluate your own circumstances.

In another example of seasonal weather altering one’s primary carry method, I’m not hardy enough to wander the cold streets of Indianapolis with my coat unzipped in the dead of winter. With my heavy coat zipped up to keep me snug while walking to and from the grocery store or corner restaurant, a small revolver tucked into an outside coat pocket becomes not a backup piece, but actually my first-line go-to.

In fact, even considering the drawbacks I listed for shoulder holsters, I keep that revolver in an Uncle Mike’s pocket holster in a weak-side, high-chest pocket on my parka, in a position roughly equivalent to a military “tanker-style” shoulder holster, because it also allows me to access the wheelgun while seated in my car with my coat zipped up and the seatbelt fastened. I know some folks who solve the same problem by adding a small revolver or pistol in an off-body carry solution, like one of the currently trendy cross-body pouches, which is apparently what we’re calling fanny packs nowadays to sound cooler and trendier.

Whether you’re choosing an off- body solution for that readily accessible cold-weather piece or tucking one into your coat pocket, just remember that you are responsible for keeping it secure from unauthorized access. You can’t just leave your fanny pack hanging on a coat tree in the corner of the office or check your coat when you go to a restaurant. Have a means of unobtrusively securing it or keep that garment or bag under your direct physical control—always. Convenience of access in the cold-weather months comes with some inconvenience in other departments, but a little planning can keep you cozy and safe.