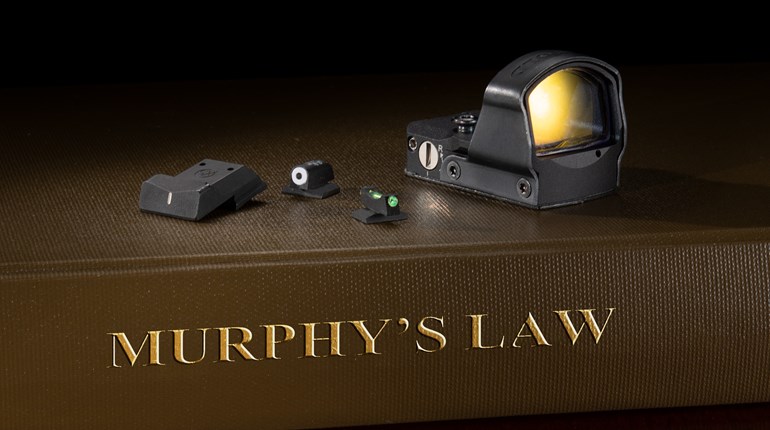

The chassis of a SIG Sauer P320 legally constitutes a firearm and is therefore engraved with the serial number. It can be fitted with interchangeable grip frames, barrels and slides.

To open this column, let’s stipulate one thing: If we are going to have laws regarding handguns, there must be some part of that handgun that has the irreducible element or essence of “handgun-ness” to it. Otherwise, simply removing one part, no matter how insignificant, would result in us having two handgun parts and no handgun, in some bizarre, reverse-Ship-of-Theseus logic problem.

In other words, without a certain part imbued with the legal “essence of handgun,” you’d take off, say, the front sight or the grip panels and be left with a gun part. To avoid this sophistry, the law decided that the frame or receiver would be the part that is the handgun itself and must have a serial number on it. (In the biz, this is referred to as the “serialized part.”)

With semi-automatics, the frame was the part that held the lockwork and the magazine, and that’s the part that was legally the firearm. The rest of everything was just the aforementioned “gun parts.”

Even in the early days of polymer-frame handguns, such as the VP70Z, Glock and Smith & Wesson Sigma, the entire frame was the handgun and complied with serial number regulations by having the number etched or stamped on a metal plate that was permanently embedded in the plastic of the frame.

The first notable departure from this was the 2011 series of pistols from STI (now known as Staccato), which had a metal piece that formed the upper half of the frame, comprising the dustcover, the part that held the lockwork and the frame rails, and then having a separate polymer part that comprised the grip, mag well and trigger guard that was pinned on. An action-pistol competitor could match their 2011’s grip size to their hand and its color to their mood without having to change the serial-numbered part of the pistol.

In the late 1990s, Steyr’s M-series of pistols utilized a removable sheet-metal chassis that carried the lockwork and formed the frame rails. The manufacturer even patented this feature. Inexplicably, it continued the then-current practice of serializing the polymer grip-frame housing.

It wasn’t until SIG Sauer introduced the DAO, hammer-fired P250 in 2007 that anyone took advantage of the possibilities of that innovation. Like the Steyr, the SIG P250 had a one-piece chassis containing the lockwork and forming the frame rails. Unlike Steyr, SIG Sauer branded this piece with the serial number, peeping out through a hole in the plastic grip housing.

SIG took advantage of this in a couple ways, selling both caliber-conversion kits as well as selling boxed sets with a full-size P250 as well as a separate compact slide assembly and polymer grip frame housing, allowing the consumer to swap the chassis containing the lockwork and serial number back and forth between the full-size and compact setups. Essentially the P250 kit buyer was getting two pistols for the price of one and a half.

Alas for SIG Sauer, the P250 launch was snakebit and required some revisions before it was good and debugged, by which time its reputation had been besmirched in the marketplace. It was never a great seller before being quietly discontinued. Steyr continued to sleep on its patent claims.

Then came the second salvo from SIG Sauer in the form of the striker-fired, polymer-frame P320. It shared some similarities with the previous P250, but the market was much more accepting of a striker-fired semi-auto than a hammer-fired DAO, and the P320 was a smashing success, to the point of winning the contract to become the M17/M18 handguns for the U.S. armed forces. Suddenly, Steyr remembered its patent and courtroom shenanigans ensued.

Leaving those aside, the “serialized chassis” is becoming an increasingly common fixture of handgun design. From the Savage Stance to the new RXM from Ruger and Magpul, it’s becoming increasingly common to find the serialized part as a small, removable piece holding the lockwork and frame rails rather than the entirety of the grip.

So, what are the implications of all this for the future?

The first ones that spring to mind for me are the legal ones. Now, I’m fortunate to live in a state that has no particular state-level firearms restrictions beyond those stipulated by the federal government. When I moved here way back in 2008, the only possession-type restrictions were an outright ban on short-barreled shotguns and the requirement to have a permit to transport a handgun anywhere but to and from the gun store, and both of those restrictions were overturned.

But, there are some jurisdictions which still languish under all manner of archaic and unconstitutional regulations. Whether it’s a waiting period, a purchase-permit requirement, a limitation on what handguns can be carried legally on a toter’s permit, or whatever, an anti-gun political jurisdiction can throw all kinds of hurdles and barriers in the path of a law-abiding citizen wanting to exercise their gun rights.

The NRA is fighting these restrictions constantly, but until the happy day that they’re all overturned, the chassis system offers a handy alternative. With a chassis-type handgun, you buy the “handgun” itself just once, and from there it’s just buying gun parts. If you buy a SIG Sauer P320 compact in 9 mm for concealed-carry purposes and then decide you want to get into, say, bowling pin shooting at the local gun club, there’s no need to buy an entirely separate handgun. You can just buy a .40 S&W full-size “Caliber X-Change” kit and swap your existing chassis lockwork into it. No need to wait out the process of buying an entirely new handgun, because you aren’t. As an added bonus, every trigger pull you put in shooting bowling pins will be practice with your CCW pistol because it’s literally the same trigger. And I mean literally in the literal sense here.

Even for those of us not living behind legislative enemy lines, being able to swap between barrel lengths or chamberings without having to buy a whole new pistol has a certain attractive charm.

Furthermore, having the serialized part separate from the grip itself has benefits for those of us with a certain … let’s call it a do-it-yourself vibe. If you got a traditional polymer-frame, striker-fired pistol and decided to break out your wood-burning or soldering iron to modify the grip texture or contours and you messed it up by not studying one of the many videos on doing it properly, well, you just junked the gun itself and would have to order a replacement frame for hundreds of dollars and go through the whole 4473 process again.

With a chassis-system pistol, you can just order some polymer grip-housing modules at $30 to $80 a piece, have them delivered, and fiddle away practicing your contouring or texturing techniques. If you junk one, it’s no biggie because your carry pistol is still intact.

One might surmise that the emergence of the modular pistol chassis could negatively impact gun sales, since, by purchasing one gun, the consumer can potentially, afford- ably, endlessly reconfigure it and never need another handgun. Maybe, but it’s also conceivable that the buyer will more readily “pull the trigger” on a purchase since the modularity inoculates against buyer’s remorse.

Let a thousand modular-chassis flowers bloom.