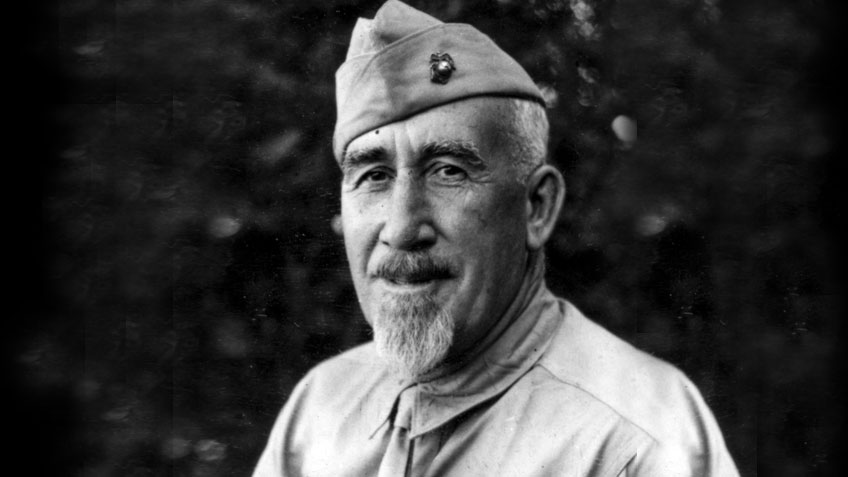

Diamond’s expertise with a mortar kept troops safe through two world wars and countless skirmishes.

To be “salty” is to be recognized as having extensive experience in nautical matters. Time spent in these duties invariably results in exposure to salt water, which evaporates to a salty film around head and shoulders. Marines have a strong identification with naval matters, so a leatherneck with a few hashmarks (service stripes) is often deemed salty. Vast troubles attend a youngster who displays the casual behavior of a seasoned veteran before he has served long enough to have a decent coating of sodium chloride. Today however, we are concerned with a man who was really salty—and to the benefit of many who were not.

Leland “Lou” Diamond was born May 30th, 1890 in Ohio of Canadian-American parents. After initial schooling there, as well as several years of railroad work, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1917.

It was just in time to make the trans-Atlantic voyage to the war in France with the 6th Regiment of Marines. Diamond served with a rifle company throughout the Marines’ World War I service at Château-Thierry, Belleau Wood, Anise-Marne, Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. This was exceptionally violent trench warfare that convincingly established the Marine Corps as an elite branch of the naval service. After duty with the Army of Occupation, Diamond returned home and mustered out. It didn’t last—civilian life was not for the veteran and he spent most of the inter-war years with the 4th Regiment in China. He spent a short tour with the Supply Department in Philadelphia, where his vast infantry experience was applied to the design of a new infantry pack. His system lasted well into Vietnam, earning more curses than kudos, as well as a hearty sigh of relief from this writer once rid of his.

Diamond was one of those old-time Marines who spent too much time in Asia, where his parade-ground roar struck terror in the hearts of young Marines who were not—in the Master Gunnery Sergeant’s estimation—squared away. Diamond was not a spit-and-polish type Marine and even wore a goatee at times, but he knew bloody warfare. His troops were more inclined to fight than shine their Fair Leather belts, but they were always get-it-done warriors. Diamond went to war again, this time with the 5th Marines at Guadalcanal in 1942. His service with that famous regiment was credited with heavily influencing the outcome of several critical fights. Gunny Diamond was a mortarman, highly skilled with both 60- and 81 mm mortars. He led a mortar section that had both types in those early World War II Tables of Organization.

The mortar is often overlooked or misunderstood among the population, but profoundly appreciated by experienced infantrymen. This is because of the mortar’s inherent lethality. It’s a weapon that delivers a cast-steel shell full of high explosive to a target several thousands of meters away. On impact (or in the air with a variable-time fuse) the mortar round explodes into multiple pieces of jagged metal that strike with velocity. In actual battle situations, a single mortar round often kills or wounds several enemy soldiers. An indirect-fire weapon, the mortar is fired by a small crew that can’t usually see the target, but is remotely aimed by an observer who can. Mortar gunnery is a complex subject that cannot be adequately described in this limited space. The gun itself is a marvel of simplicity and is really nothing more than a steel tube, closed off with a ball-shaped cap at the bottom end. The ball fits into a socket in a heavy piece of steel called a baseplate. There are no moving parts in this arrangement.

Mortar shells are heavy and come in strong cardboard tubes. Shaped somewhat like cartoon bombs, with a pointed front end and fins at the rear, the mortar shell has an igniter in its base. This is essentially an oversize primer that will flash with fire when struck. Also, the shell comes with strips of propellant, wired onto the fins. The gunner drops a round down the upright mortar tube and falling by its own weight, the base of the round strikes a fixed firing pin at the bottom of the tube. The igniter flashes and ignites the propellant, which produces high-pressure gases that drive the cartridge up and out of the gun. Tilted slightly away from straight up, the mortar round describes a steep arc and comes roaring down on the enemy. There is a bipod close to the top of the tube that braces two legs against the ground. It has the means to vary the angle and direction of the tube. Changing the number of propellant increments changes the range. It is remarkably simple and quite effective.

The mortar was Lou Diamond’s pet weapon. Over the years, the Marine Corps has used several sizes of these things. From the little 60 mm and bigger 81 mm tubes of World War II, Korea and Vietnam, through a dalliance with the 4.2-inch mortars of Korea, to the 120 mm guns now in use, we have depended on these weapons. The Master Gunnery Sergeant’s skill with them drew strong formal praise from no less than the commanding general at Guadalcanal, Alexander Archer Vandegrift.

But, his skill was also the source of one of those persistent war stories that are such a big part of Marine folklore. Japanese ships were often found at close range in the 1942 Guadalcanal campaign. I can recall a (quite) salty Gunnery Sergeant facing my platoon of shiny new Second Lieutenants at Basic School. He was an instructor and his subject was mortar gunnery. Quietly, he related the tale of how Diamond had sunk a Japanese destroyer by dropping an 81 mm mortar round down her stack. Over time, I have noticed that the emphasis provided by successive generations of salty storytellers is starting to weaken. For many decades, I have looked at appropriate histories to verify this story and found nothing. It is possible, I suppose, but I did not see it and I don’t know. I have been on both sides of mortar fire and mightily respect this unique kind of fightin’ iron.