For more than 70 years, the gun industry has been striving to make firearms lighter in weight. The practice continues today with the use of polymers.

Quite possibly, some early predecessor of modern man discovered that fighting for survival is easier when you used tools. And, thus was born the arms industry. At first, it was a search for a rock of the perfect size with which to smack an enemy, but it evolved further over the ages. When one guy put a handle on his rock—thereby creating greater leverage for his blow—he was an arms genius. I think you can follow how things evolved and developed over the millennia. As it applies to personal-defense weapons, there are milestones like the discovery of ways to make better edges for cutting weapons, the discovery of gunpowder to launch projectiles and eventually firearms cleverly configured to fire several times in sequence. It is all progress. This month, we’ll look at a class of handgun designed to be used sparingly.

Everyone who developed an improvement in a firearm for personal defense came up hard against an inescapable truth. If the new arm is truly effective, it’s going to be pretty big and really heavy. You can’t escape the fact that you are launching a chunk of metal at a speed the human eye cannot follow. If that oft-quoted law of motion is true (it is), then there has to be an equal and opposite reaction. This is the phenomenon we notice as recoil. Depending on the level of felt recoil you can accept, the lighter you can make the gun. In these civilized times, most defensive firearms spend more time in the shooter’s holster than the hand—more carried than fired.

It is accepted that a defensive firearm must be habitually carried, so it is likely that the smaller, lighter gun is more likely to be there when you need it. For decades, the major handgun makers developed steel that could be economically machined into the various components of a gun. This came to be what you used when you were in the gun business. Other metals were also used, although not often and not for any structural part of the gun. During World War II, the American firearm industry was on three-shift status, cranking out millions of various steel arms for military use. When the final gun sounded in 1945, the American arms industry had to take time to catch its breath and re-tool to make civilian and law enforcement firearms. When it did that, one of the most important innovations in gun-making history emerged—Colt Firearms introduced lightweight handguns made of aluminum alloys.

During the year 1949, Colt was updating its civilian product line and casting about for new products. While the much-beloved service pistol—the Model 1911A1 chambered in .45 ACP—enjoyed a fine reputation, more than a few G.I.s thought it was too heavy. At 39 ounces, it was indeed a hefty handgun. So, Colt used a carefully selected aluminum alloy (which it dubbed Coltalloy) to build a 1911-style 9 mm pistol that weighed a mere 26 ounces and was .75-inch shorter than the government model in the barrel and slide. It was named the Commander, and Colt has made them for 72 years. Oh yeah, and when the government sort of lost interest, it added .45 ACP and sold even more. The Commander is an unquestioned classic, but I can recall articles in several of the gun magazines of that period solemnly worrying about the lightweight’s durability. Seventy-two years.

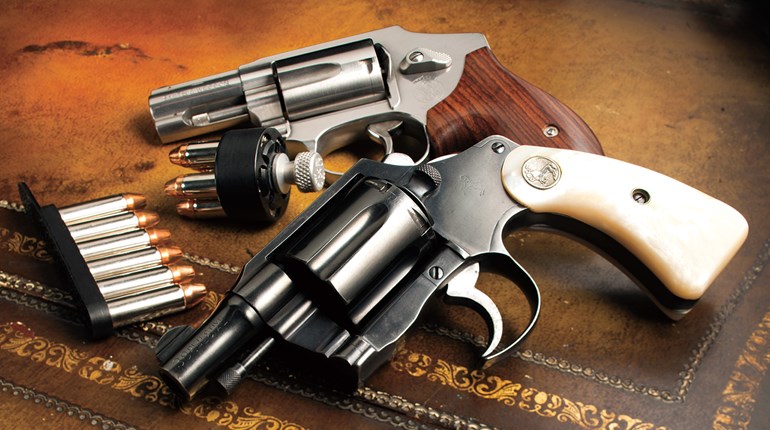

Most of this interesting stuff happened beginning in 1949 to 1950, but there’s one more Colt that we need to check out. The company made an ultra-popular little revolver back in the pre-war era. Based on the company’s Police Positive (D-frame), the Detective Special was a medium-frame, six-shot, DA/SA Colt with a 2-inch barrel. It was well-named in the sense that it was popular with undercover peace officers. Then, the company unveiled a new wheelgun given the distinctive name of Cobra. This little revolver was a dimensional twin to its predecessor, but its frame was Coltalloy. The Cobra weighed in just shy of 1 pound. The new, lightweight, compact revolver was an instant hit.

And then there was an even wider array of lightweight pistols and revolvers stamped with the intertwined “S&W” of Smith & Wesson. It started with its 1950 Chiefs Special, followed closely by the Bodyguard and Centennial, all of which were built on the company’s newly developed J-frame. When the U.S. Air Force, created in 1947, wanted lightweight sidearms for flight crews, Smith & Wesson built a number of special revolvers in five-shot J-frames and six-shot K-frames. On a milestone gun called the Model 39, Smith & Wesson used aluminum for the first DA/SA 9 mm semi-automatic pistol made in America. This period was an exciting one for serious students of the gun.

We are presently living in a time when a large percentage of current production handguns are lightweight by virtue of polymer construction. This entire effort—weight-reduction—has nothing to do with enhancing any aspect of the gun’s performance. It’s all for the comfort and convenience of the shooter for the time when he or she isn’t shooting.

So what? If it’s easier to carry, it is more likely to be carried. And it’s still fightin’ iron.