While the Smith & Wesson New Departure Safety Hammerless’ anemic .38 S&W chambering provided insufficient terminal performance for Rex Applegate, the encounter resulted in the firm’s creation of the .38 Spl. J-frame revolver.

Handgunners whose work requires them to habitually go heeled may have problems in selecting a gun. But, those who must carry, and can reasonably expect to use the gun, face even greater ones. If the easy-to-carry, easy-to-draw, easy-to-shoot gun lacks on-target stopping power, the guy who made the choice just might be the victim of a poor choice. This is the story of a legendary American soldier and the gun that functioned perfectly, but didn’t stop the fight—as well as the gun that grew out of it and stopped many fights.

We need to start at that point in history when the gunmakers were starting to build small, lightweight guns. It was the middle of the frontier era, where Smith & Wesson’s main fighting handgun was the Model 3 series (American, Russian, Schofield and Number Three). These might be called “holster” guns because they would best be carried in a sturdy leather holster. In the 1880s, the company introduced a compact pocket revolver that was small enough to fit in most of the pockets of men’s clothing. A hinged-frame, five-shot revolver offered in .32 and .38 calibers, the gun was officially known as the New Departure Safety Hammerless and unofficially as the “Lemon Squeezer.” It had a completely covered, spurless hammer activated by a double-action-only trigger system. For safety, the gun had a grip safety on the backstrap and could only be fired by the firm pressure of an adult hand.

This little gun was—in its day—a popular style of revolver, with similar models made by many other gunmakers, both here and abroad. Smith & Wesson made them in a variety of barrel lengths, with the most popular ones having shorter barrels. The manufacturer advertised the 2-incher as the “Bicycle Gun” for its use by bicyclists against attacking dogs. Introduced in the 1880s, this remarkable little gun was still in the catalog in 1940. While Smith & Wesson and Colt also made 2-inch, self-defense-oriented, solid-frame revolvers, the more compact Safety Hammerless was still competitive. Prototypes exist of a larger-frame hammerless revolver in .44 Russian, and I often wonder what might have happened if that variant had been produced in quantity.

One well-known user of the Safety Hammerless was COL Rex Applegate. The son of a prominent pioneer family, Applegate grew up in rural Oregon as a hunter and fisherman. He was strongly associated with firearms by virtue of an uncle who was as an exhibition shooter for Peters Cartridge. Applegate graduated from college just before World War II began and found himself in the Military Police. In those times, only tall men served in the MPs, and Applegate was 6 feet, 3 inches. Still a lieutenant, he was called to Washington for an interview with a general officer named Donovan. William J. Donovan commanded the OSS, which ran a wide variety of covert operations throughout World War II.

Applegate’s orders were simple: Learn all there was to know about close combat. There followed a frantic, but fruitful, period of intense study of how to cut throats and shoot hearts. He also participated in several commando operations during the war.

The post-war period found Applegate running a sporting-goods-import operation in Mexico. This business found him traveling in Central America and Mexico a great deal, and he routinely went armed.

His favorite revolver was one of the Smith & Wesson Safety Hammerless models chambered in .38 S&W with a 2-inch barrel. I have handled the gun, which is quite important in fighting-handgun history. He carried the gun in an unusual holster from S.D. Myers named the Detective Wonder Holster. It held the gun in a muzzle-up position and was very fast to draw from under an untucked shirt. As you might have guessed, he had need of the gun one particular time, and we are about to look closely at what happened. There have been several accounts of the fight published recently and I would like to add his version, as told to me in his study one evening before he passed away.

On an evening in the late 1940s, Applegate went out to dinner with an officer in the Mexican Army who was in uniform and carrying a .45 ACP 1911 in a flap holster. Applegate was packing the Smith & Wesson Hammerless in the Myers rig. Their meal concluded, the two officers were in the lobby at the front of the restaurant, about to leave. The front door burst open and a man attacked them with a machete, coming right at them with an upraised blade. Applegate did not hesitate. He drew the little Smith & Wesson and began shooting. Applegate fired five consecutive shots and hit his assailant five consecutive times. This failed to stop him, but the army officer finally got his 1911 out and working. The unidentified attacker went down to 230 grains of jacketed lead. Nobody ever figured out why the man behaved as he did.

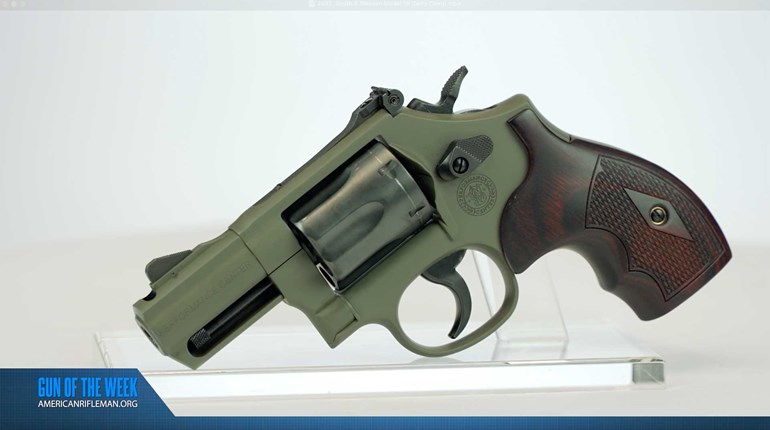

It is clear the ammunition—.38 S&W lead round nose—failed utterly. And, shortly thereafter, Rex Applegate and his friend W.H.B. Smith (author of “Small Arms Of the World”) were conversing with Carl Hellstrom of Smith & Wesson. The result was a revolver that took more powerful .38 Spl. ammo and had the internal-hammer feature. Since then, they have made it work with .357 Mags.

In other words, proper fightin’ iron.