Have you ever known a shooter who likes to miss? All shooters who bother to spend valuable time training do so with the intention of improving their skills and the desired result of being able to perform those skills under pressure.

In the training environment, there is no more useful, double-edged training tool than trending mistakes. Dreaded by most and embraced by the elite, error patterns provide insight into what you’re doing wrong—and why.

What are the five most common error patterns and how can they teach you to isolate weaknesses, iron them out of your shooting process and convert them into your most reliable strengths?

American philosopher John Dewey famously said, “Failure is instructive. The person who really thinks learns quite as much from his failures as from his successes.” This quote captures Dewey’s belief in experiential learning, where both successes and failures contribute to deep understanding and growth. He saw mistakes as essential to the learning process, as they encourage critical thinking and adaptation.

The top 1 percent of shooters on the planet—the likes of grandmaster competitive shooters and special operations asymmetric warfighters—also see failure as essential to hone their skills to the razor’s edge of human performance. Through the painstaking effort of trial and error, they work tirelessly to eke out that one drop of performance that will take them to the next level.

Every shooter, including that 1 percent, misses shots. Of course, the shooter with a 100-percent hit ratio does not exist. The differentiator between those without belly buttons and we normal air-breathing, humanoid earth-walkers is the frequency and also the severity of the error. Of course, the higher up the shooting-performance ladder you climb, the lower your volume of errors, and instead of being completely off the target (novice), the hits are near misses (the 1 percent).

Mistakes are the unspoken tutors that whisper through each stumble, guiding us where conventional teachings cannot reach. In the brittle pause that follows an error, where there is a fertile space, where the mind, stripped of pride, meets raw understanding.

It’s about leaving your ego at the door. By making mistakes, you are forced to confront the limitations of your own understanding, to lay aside pretense, any emotional attachment and defensiveness, and to engage directly with the lessons embedded within your own missteps. Each error brings clarity, offering up nuances and depths that no manual, lecture or secondhand advice can replicate. Like Michelangelo refining a marble sculpture, mistakes chip away at the excess, gradually revealing the truest form of how you envisioned it.

The humbling nature of mistakes drives a deeper kind of learning, one that is personal and impactful. Mistakes offer a connection with failure that builds resilience; they push you to dig into the why and how, to truly grapple with the intricacies of each error. Through this process, learning becomes embodied—a true experience—making the lessons indelible and etched into your memory. Where successes can be brushed off as luck or chance, mistakes demand engagement and reflection, establishing a connection to the shooting process that is profound.

Errors demonstrate that complexity is what defines simplicity. This is the learning that lasts: not the gloss of ephemeral success—a one-off catching of lightening in a bottle, but the depth of overcoming. True progress.

Errors usher you to the next skill level because they force you to reconsider what you thought you knew. Your every misstep exposes the gap between intention and reality, requiring you to adapt, rethink and sometimes even unlearn. In that iterative process, you evolve, gaining greater understanding, skill and performance. The purpose of error patterns are ultimately to develop one’s shooting performance and their analysis are essential to effective diagnostics.

Certain criteria are recommended to best learn from error patterns. The first of these is that there cannot be fewer than five rounds used to measure. A single round could be chance, a second perhaps luck. Five rounds is the magic number, because a contiguous string of fire demonstrates the continuity, repeatability and durability of a shooter’s mechanical skills.

The second criteria requires that there is little or no external influence or extenuating conditions impacting the laboratory, such as extreme inclement weather like driving rain where you can’t see your sighting system, gale-force winds causing the target to bounce around or debilitating cold where you can’t even feel the gun in your hands.

Lastly, the shooting should be a challenging, yet attainable skill. Reaching for the moon—like a novice shooter attempting to put five rounds on a business card at a distance of 25 yards from the holster in less than 5 seconds—is an unrealistic expectation. Five rounds, an amenable shooting environment and realistic expectations are conducive to meaningful diagnostics.

In the world of performance shooting, diagnostics—more art than science—form the backbone of skill building. No two shooters are the same, each presenting unique physical and mental traits, leaving little room for absolutes. Yet, common shooting errors appear consistently across strings of fire, creating recognizable patterns that support effective diagnostics.

As such, there are at least five common error patterns that can identify and isolate a weakness, afford you the opportunity to work them out of your shooting repository and convert them into your most reliable strengths. Listed in the most commonly occurring order are the lost-zero pattern, a cross-sector pattern, single sector patterns (horizontal or vertical stringing) and a percentage pattern.

Most professional classes begin their training regimen by checking zero. However, every now and again there’s the one shooter who, at the end of day one of a five-day training block, just cannot figure out why he or she has been shooting slightly left all day. As a result, the downside to this is that they lost at least one entire day of training, has blamed nobody but his of herself for their inadequacies which, in turn, attenuated their confidence in their abilities. Nonetheless, all of this unnecessary baggage can be avoided by recognizing a lost-zero pattern.

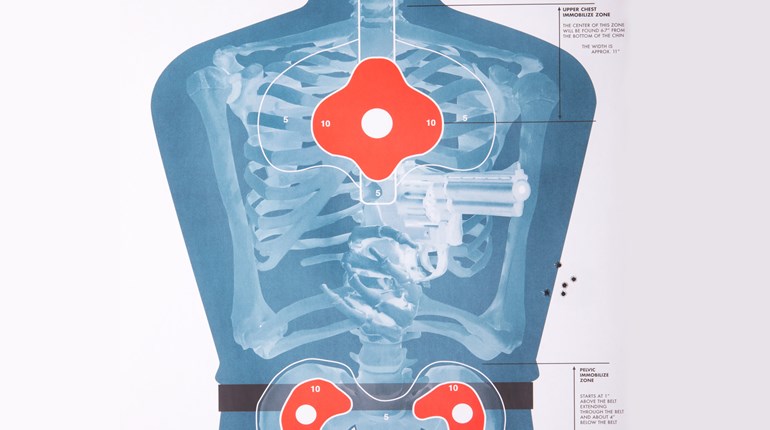

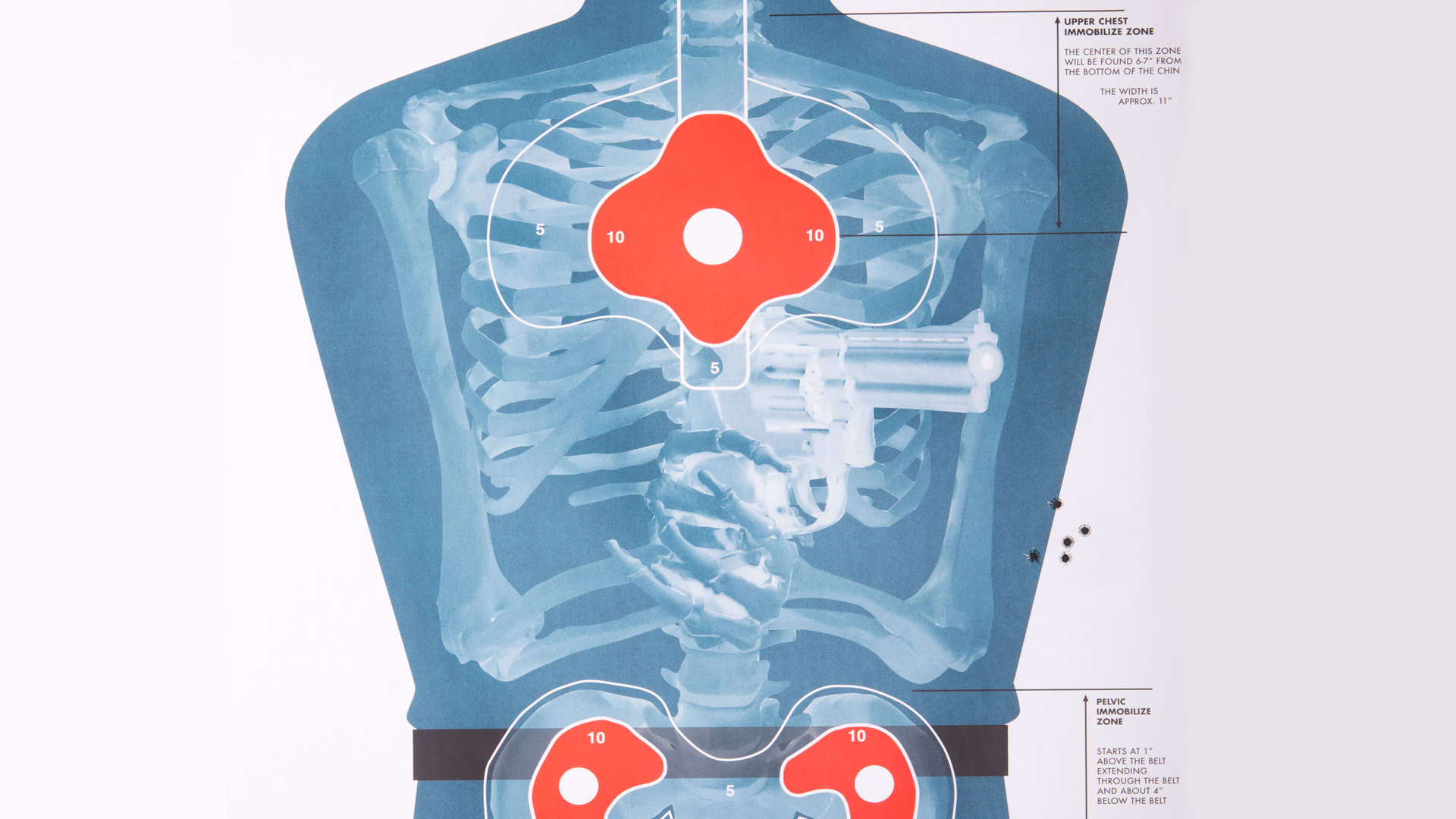

Be on the lookout for a pattern of hits that, although they may form a great group, are consistently found in the wrong position on a paper target. The “A” answer is to simply reconfirm zero during a break. Reconfirming a shooter’s zero facilitates eliminating the firearm as the culprit. It restores shooter faith and confidence and refocuses one’s accountability.

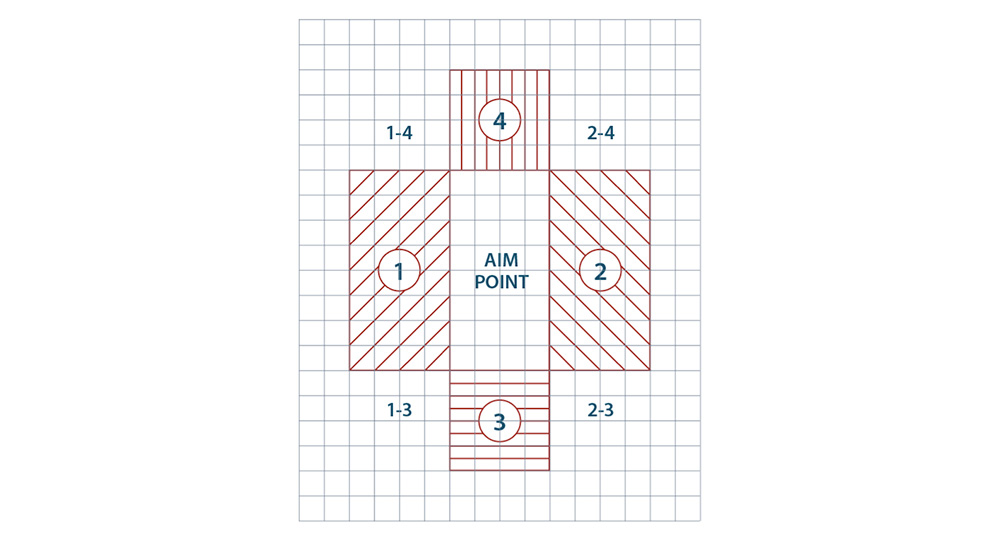

Although not as common with irons, this is often seen with carry optics and should be considered a training factor as such. If you set your aimpoint within a grid and parse that grid into sectors, it will provide a diagnostics-reference framework.

A cross-sector pattern describes shots trending in the 1-3 target area, for example. A trending pattern of shots in the 1-3 area for righthanders and 2-3 for lefties might suggest a change in grip pressure.

The sectors are numbered in order of shooter control. Trending errors in sectors one and two suggest a lower control level, whereas errors in sector four (what Rob Leatham calls “professional misses”) generally reflect greater control. Trending errors in multiple sectors—like 1-3—suggest the lowest level of control.

Grandmaster Travis McCamish describes grip pressure as the amount of force applied with the fingers and the hand to the firearm. Wrist tension or rigidity, which manages muzzle flip in recoil, is also considered part of the grip. He further defines structural support, separate from grip, as that anatomy from the forearms through the upper torso and to the gun belt.

Although failure of the mental and visual processes can and do significantly contribute to erroneous round placement, mechanically speaking, most cross-sector round-placement errors suggest either grip or structural failure or possibly both.

Although delivered on target at an appropriate elevation, a shooter may string their shots horizontally, distributing rounds through sectors 1 and 2. Observing an occasional left or right flyer isn’t much of a problem; however, should you see a trend toward a single sector, then it becomes an issue that should indeed be addressed.

Single sectors 1 and/or 2 are where the shooter may have a visual processing challenge, which can be readily corrected by asking them to remain target-focused and running a couple of target-focus drills should knock that out. If, however, he or she lost mental focus, then it’s a mental-discipline issue.

However, if it ends up being a mechanical process, it could mean either grip or structural failure. It’s most likely not a timing issue, as sectors 1 and 2 suggest more of a lack of control at a certain speed.

To iron this one out, slow the pace down and speed it up like a rheostat until you observe the same pattern. The faster you shoot, it’s inevitable that one or more of the wheels will fall off. At that point, you should be able to identify which wheel and its corresponding remedy.

Even though he or she may deliver rounds along the centerline, you happen to notice vertical stringing above or below the aimpoint as opposed to horizontal stringing. The fact that this shooter is stringing vertically means they’re a bit further along in terms of control (no longer afflicted by sector 1 and 2 trending flyers) and this error may be either a matter of timing or muzzle diving.

Trending rounds in sector 3 suggest the shooter may be “driving” or “steering” the muzzle in a downward direction below the visual center of the intended target where such added input is excessive to the action cycle of the reciprocating slide in recovery to alignment. You may want to ask the shooter to “allow” the slide to return as opposed to inducing unnecessary input. You may want to ask the shooter to “lighten up” the recovery process, which will help prevent that added downward driving force misaligning the muzzle during the press.

Trending rounds in sector 4 usually suggest a timing issue, where the shooter is predictively or proactively anticipating recoil recovery return and has most likely mistimed the press. The shooter must strive to time the rise and recovery to alignment process in such a manner as to align point-of-impact with point-of-aim on the vertical plane.

Single-sector patterns suggest that you may very well find either a grip-pressure change or a structural stability issue for sectors 1 and 2. Whereas vertical stringing in sectors 3 and 4 suggests either a matter of timing for a high-miss pattern or driving the muzzle below muzzle flip recovery for a low-miss pattern.

Errors usher you to the next skill level because they force you to reconsider what you thought you knew. Every misstep exposes the gap between intention and reality, requiring you to adapt, rethink and sometimes even unlearn.

Commonly presented as “three in and two out,” this pattern demonstrates a 60-percent success rate. For example, you have three of the five rounds right where you want them and the other two are outlaying flyers in one or more sectors. Specifically, what most shooters strive for is an 85 percent or greater performance, so the 60 percent—although this may be “good enough for government work”—is certainly not a master-class performance level.

Although you should not rule out a durability (failure of the shooter’s mechanics), the percentage pattern suggests a lack of mental or visual focus warranting more discipline.

Evenly distributed “shotgun” patterns (as opposed to the percentage pattern) get wider as you push to the edge of your control envelope, which is perfectly acceptable and exactly what you want. When pushing your limits results in a general grouping, only spread out, that is a good thing. When that grouping starts trending toward a particular sector or cross-sector, then you may be observing an error pattern which can be addressed. It’s important to note that this is an observation from a diagnostic perspective and reading error patterns is an integral aspect of diagnostics.

The purpose of error patterns and their corresponding diagnostics is to help push a shooter outside of their control zone. You can not fix what you can’t see. If you are shooting perfectly and not missing anything, then you are not pushing yourself hard enough. If you want to blow past your current performance envelope, you need to start making mistakes.

Pattern recognition can point a finger to probable cause. The usual suspects might be the gun (lost-zero pattern), a wheel falls off (mental or visual process or focus or mechanical), durability, consistency, repeatability and whether you can remain in or out of control.

Master-level shooters and instructors utilize errors as a learning tool to increase their control and strongly encourage their students to do so as it’s the only way to step outside your comfort zone. Therein lies the deepest value of error pattern recognition.

What makes error patterns the ultimate teacher is two-fold: One is to support and enhance your diagnostics. The second is to help you push past your current skills envelope by finding your efficiencies which further develop your control level. To that end, error patterns are considered a tremendously useful tool and indispensable training asset.