One of the questions I am most frequently asked after a student completes a training course is “How do I get better?” It’s a great question. For some, they performed well in the course and want to continue to improve. For others, they failed to perform well and want to know what they can do to improve. I look at myself as a life-long learner, so I love hearing this question. Over the years, I’ve fine-tuned my answer in an effort to provide an actionable response. The answers I provide are practical and, in my opinion, easy.

Start by defining the investment you are willing to make. Set challenging, but attainable goals. Document and critique all your performances. Train with people better than you and help people who struggle. If you can follow this advice, your practice will not only be effective, but efficient.

The problem with high-intensity shooting courses is there is a lot to cover, but not an equal amount of time and, from the instructor’s standpoint, we need to make concessions. One thing on which I do not compromise is providing students with the tools for continued education at their own pace. I believe the real training begins once they leave the course. Don’t make the mistake of thinking there is no room for improvement, or that a single, 16-hour course every couple of years (or less) will suffice.

It is also a mistake to think you don’t need to practice. Very few can leave a course and not need to practice. Part of the reason for some not “needing” to practice is because they have committed to regular practice in the first place, so the need is implied.

I like to remind myself just how imperfect I am by starting a new hobby every 10 years. It is said that it takes approximately 10 years to truly master a skill, to be at the pinnacle of performance in said study. My experience confirms this at a general level, but there will always be outliers that either reach mastery sooner, or take much longer. The point is it takes time—even if you don’t want to gain mastery, just being competent is still time-consuming. What I’ve taken away from building new skills is a better sense of how I learn and make progress. It has, in some cases, allowed me to shorten my overall learning curve. I still struggle, but part of that conflict is the reason I continue to challenge myself. It is easy to become complacent if you don’t.

A big mistake many new shooters make is not aligning their expectations with reality. If you want to be a good shot, you will need to shoot a lot. If you want to see the gains, you will need to invest in ammunition and time. I recommend looking at an hourly investment spread out over years. You can choose one, three or five years for the initial break-out period. It is during this period where you will see the most gains, since you are starting from a low knowledge and skill base. I feel one year is too short, and five years is asking a lot, so three years is a good compromise. Whatever your break-out period, chunk it into months and give yourself some realistic time-off blocks.

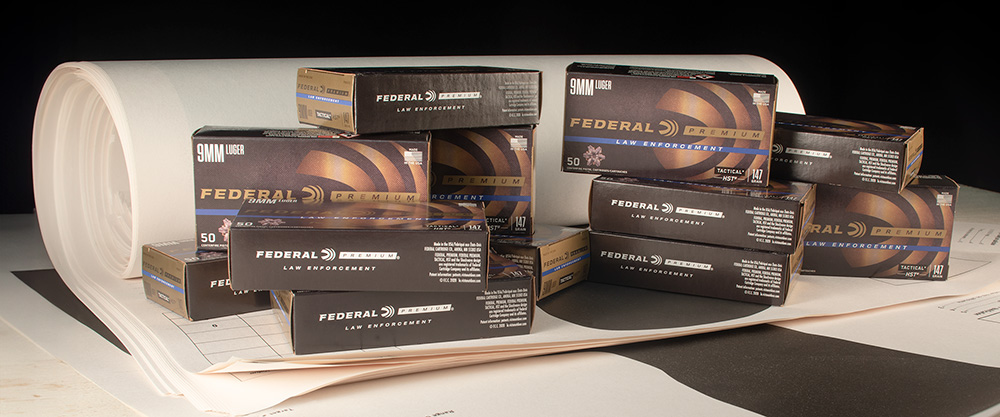

I generally plan around 10 good months of training out of the year. During these 10 months, I aim to get a minimum of 30 to 40 hours of live-fire formalized practice. Over a three-year period, that is 120 hours. Ideally, I look for a minimum of 80 hours of formalized practice. The last variant to our equation is the number of rounds I expend over this break-out period. I typically fire 100 rounds per hour of formalized practice, but I think a more reasonable expectation is 50 rounds per hour. Throughout a three-year break-out period, that would be approximately 6,000 rounds. This is what I mean by being realistic with your expectations. It will not only take a time investment, but an investment in ammunition as well, which happens to be a financial investment.

There are no real shortcuts to reaching mastery, but there are some tried-and-true methods to create a more efficient pathway.

It might seem odd to start with the investment over the goals, however when the investment is considered first, it helps keep the goals realistic. Too many times when the goal is all you think about, the investment is overlooked, which can lead to failure and frustration. This way, the expectations are kept in check by the actual needed investment in time and money. Creating challenging goals becomes easier this way.

It may seem alluring to want a sub-second draw from concealment, and I’m all for elite performance such as this. I’m bound with guilty knowledge of how to get there and most fail to reach their goals not from lack of effort, but starting with unrealistic expectations in the first place. The goal also does not need to be a specific outcome. Since we are planning for an unknown, unknowable event, the goal could even be pointed in the wrong direction. Instead, consider the goal as total rounds fired. The more quality rounds fired, the more you can develop your overall skill set.

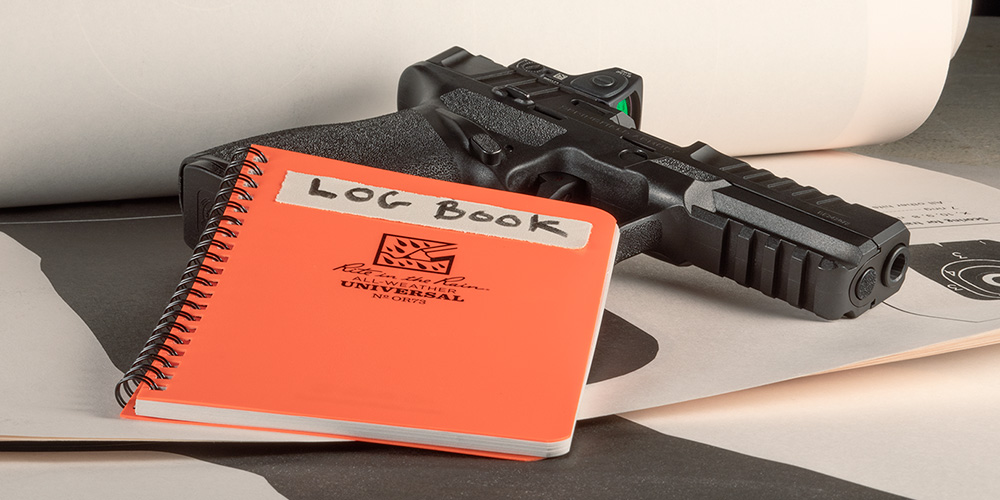

There are only so many drills one can practice. Inevitably, some will be repeated. That is a good thing, since it will allow for the observation of repeated performance. From the very beginning, the literal first round fired, start documenting. Create a tracking form or logbook that can be periodically reviewed to monitor progress.

I typically shoot what I call a “cold drill” as the first drill for all my practice sessions. I change this cold drill up every quarter, but it allows me to monitor my performance without falling into the training trap, which is only training the drill and not the skills within the drill. I will document as many variables as are relevant, such as the overall time, score, distance and type of target. When I start the next practice session I will review my past performance—“What did I do wrong or poorly?”—in an effort to make improvements. If I shot it slower than I feel I’m capable, I make the effort to go faster. If I scored below a certain threshold, usually 90 percent (75 percent for beginners), I work on my accuracy by spending a bit longer perfecting the shot(s). If I find myself somewhat stagnant, I change out one of the conditions, such as distance. Maybe I’m struggling to hit my 90-percent threshold. Closing the distance can help me get over that hurdle with the added benefit of a new goal, which would be to eventually perform the drill at the prescribed distance.

Playing with these variables—what I call scaling—can be immensely helpful at not only improving, but staying motivated. Too many failures can have a negative impact on the overall goal. However, just enough failure is great to keep you reaching and working harder.

One of the best things I did to help reach new levels was accepting an invite to shoot with someone who was without a doubt better than me at every level. It was humbling to be sure, but I went into it with my eyes wide open thinking of it as a great opportunity to learn. As our practice sessions grew, I could see my shooting improvements grow. There is plenty of research indicating that working with people better than you will lead to your own improvements.

I believe there are two big reasons for this phenomenon, and the first is recognizing your own shortcomings. When you see someone do something better, it helps break through some self-imposed barriers. It becomes almost accepted that a given performance level is as good as it can get, similar to when the 4-minute mile was broken. Until then, it just wasn’t something imagined. Then it became common practice, because the trail has been laid. I watch and ask questions to better understand what they are doing, but also what I’m not doing. Plus, having a pair of expert eyes on you to provide feedback is immensely valuable.

The second reason is motivation. When you get into these groups, there is desire to do the work. When someone suggests a range day, you are already thinking about how you can make it happen versus coming up with excuses to avoid the rendezvous. There can even be a level of competitiveness knowing others will be “getting better” in your absence. The last thing you want is to be left out of all the fun, and it is truly enjoyable to get together with other like-minded individuals who only want to see you succeed.

If you want to see the gains, you will need to invest in ammunition and time.

There’s an old saying, “if you want to master something, teach it.” I find so much value in this concept that I search out ways to teach in other areas of my life. To teach something requires a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. It requires something of a reverse-engineering process. Instead of teaching what you know, teach how you know. This requires the ability to explain concepts from a different perspective at a fundamental level. At times, there is a personal recognition of gaps requiring further understanding to teach. I further cultivated my understanding of the subject and reinforced my own beliefs that I share in an effort to teach.

There are no real shortcuts to reaching mastery, but there are some tried-and-true methods to create a more efficient pathway to such a goal. Start by defining the level of investment. Create goals for yourself that push the boundaries, but are also achievable. Take notes on everything and review them as a way of improving your performance. Find someone or a group of individuals better than you and soak up their knowledge. To truly gain mastery, teach. Find someone who is interested in the subject and offer to share your time and experience. This formula has provided solid results in all areas of my life, not just my profession. Even if these tips are not followed wholly, individually they can produce results. Nonetheless, imagine what can happen if all of them are followed.