Like hearing, hair and good knees, we take eyesight for granted right up until it begins to wane. I speak from experience on each of those points. I used to swear that I had eagle eyes. Then, in my late 30s, mild headaches led to an eye exam, revealing that I was suddenly “qualified” for Army-issue reading glasses. I was still an active-duty sniper at the time, so this was not exactly good news. But, my eyes were still strong enough to shoot without correction, so it was only a nuisance. In the intervening years, I’ve landed solidly in the category of shooters who have neither good vision nor that which can be corrected through medical procedures. As a result, we struggle to find ways to continue seeing those things critical to good shooting.

According to the Mayo Clinic, the presbyopia that often makes it difficult to focus on near objects is a natural part of the aging process. Most people start to notice this problem in their 40s, followed by a couple decades of worsening before it levels out. Why this happens is not as important as the effects it has on our shooting. At best, it causes a lag in focus time when one’s eyes transition between objects at different distances. As it gets worse, focusing on anything up close can become impossible without correction. For rifle work, this usually becomes problematic when we can no longer see our sights, dots or reticles in conjunction with whatever we’re aiming at.

But, that’s not the only shooting problem created by weakened eyes. Small things like variable-gas-system adjusting screws, power settings on accessories and cartridge-case headstamps become increasingly difficult to discern too. I knew I was in trouble when I had to replace the tiny, 8-point font “DOPE card” affixed to my rifle’s stock with a strip of paper containing hand-written, half-inch tall numbers and running the length of my freefloat fore-end.

I’ve had enough eyesight conversations with friends, family and customers to know I’m not struggling alone. If you happen to be a new member of the seasoned-shooter club, but have yet to figure out how to manage the poor-eyesight “perk,” here are a few pointers that come from the collective experiences shared in my discussions.

Open sights

If your front sight has a hood, removing it can be beneficial once your ability to focus on the blade diminishes. Likewise, if the front sight isn’t already as far forward as it can be, increasing the sight radius can add clarity to the picture. Exchanging that pin-size front post for the widest type made for your sight is another possibility. Many people also find that using a peep-style rear aperture further helps the eye focus on the front post. A bright dot, stripe or luminescent treatment can help find the sight, but it usually doesn’t make it appear any clearer.

Electro-Optics

In general, a smaller center point—2 MOA or less—and the least amount of illumination needed to see the reticle are good starting points for a dot sight. You may also find that your “weak” eye is now stronger than your usual shooting eye, which would make a switch to other-handedness at least worth considering. If your rifle wears a low-power magnifier, removing it should be helpful if your red dot looks more like a red star-cluster under magnification. For shooting needs that require extra power, using the magnifier behind a holographic sight (EOTech HWS, Vortex AMG UH-1) will likely present less of the distortion seen in a magnified reflex sight. When shopping, try to sample different sights before buying one in hopes of finding a model with a clearer aiming point. Some folks find that other reticle colors, such as green or amber, are better than red.

Magnified Riflescopes

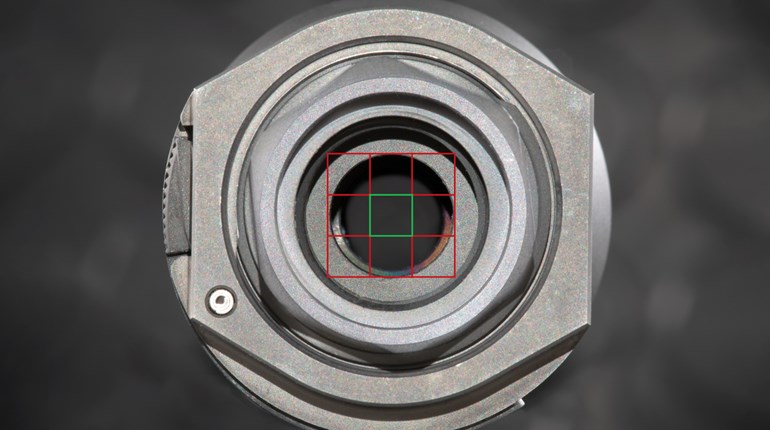

Thankfully, most magnified optics have diopter adjustments that allow reticle focus to be fine-tuned. If your optic also has a parallax adjustment, the target image can also be brought into clearer focus when changing target distances. With fixed-focus scopes, you’re left to contend with whatever the manufacturer determined to be the best settings. Trijicon’s ACOGs are good examples of this latter group and, their excellent lenses and low magnifications are easy on weakening eyes.

That brings us to another point: Dialing down scope power can also help clear things up. If this seems counter-intuitive, I’m with you. One reason for the apparent increase in clarity is that at lower powers, more usable light comes through to the pupil. I have to fight the urge to go to the highest power setting when my eyes seem to be straining, but lower powers end up being better for me—so long as the reticle lines are big enough to see clearly. For example, at low power I can no longer see the .06-mil “thick” lines that make up the H27 reticle, which was designed by some near-deaf, bald jerk with bad knees when he was still developing and testing sniper systems in the Army.

Ballistic-drop-compensating (BDC) knobs can be particularly hard to read when a scoped rifle is shouldered. When your reticle allows it, managing elevation and windage adjustments in the reticle instead of with knobs is a practical solution. Another is to have custom knobs made with larger numbers. If they’re unavailable for your riflescope, companies like customturretsystems.com and ballistix.ca offer custom, adhesive turret labels that are tailored to your optic and specific ammunition.

Glasses

Magnified shooting glasses are the next stop on the eyesight fun train. Inexpensive “readers” usually lack ballistic protection or have the magnification in the wrong portion of the lens to be useful for rifle shooting. The best bet is to visit your eye doctor to ensure you don’t have any other issues that require medical attention, in addition to obtaining a proper prescription. Finding an optometrist or ophthalmologist who understands rifle shooting may be challenging, but they do exist. Lacking that, I have found that simply explaining what I need to see at different distances and the types of sighting devices I use is enough to get the correct prescription.

If correction is needed for both far and near vision, taller lenses seem better-suited for ensuring the different magnification sections are in the right spots for aiming a rifle. This can be a trial-and-error process, so opting for a less expensive prescription lens provider may be a good idea when starting down this path. Be sure that any shooting glasses meet or exceed the ANSI Z87.1 (or Z87+) ballistic-protection specification.

Unfortunately, there’s no panacea available for the difficulties encountered with aging eyes. With luck though, some combination of these tips will help you see clearly and shoot well for many more years to come.