At a recent gun show I floated by a table where several folks were eyeballing a Mossberg Chainsaw—you know, the pistol-gripped Model 500 variant with the over-the-barrel foregrip that makes it look like Leatherface’s favorite killing device. But, they weren’t arguing about the grip of dubious practical design. No, no, they were talking about the jack-o-lantern-looking muzzle brake on the end of its barrel. Much like the old Miller Lite commercial (tastes great vs. less filling), one guy was saying it was to reduce recoil while the other was arguing that it was to hide the shotgun’s muzzle flash. I walked on by without saying a word, of course, but nonetheless mass confusion remains. And the source of that confusion is: What the heck are muzzle devices on shotguns used for, and do you need one?

Generally speaking, there are a half-dozen uses for shotgun muzzle devices, including: Adjusting choke, reducing recoil, hiding flash, breaching doors, busting bad guys and looking mean in a catalog. Here’s my take on each type of muzzle device.

Choke Adjustment

The Poly-Choke has been around since the 1920s. This unsightly aftermarket apparatus, like the Cutts Compensator, was touted to let shooters adjust the constriction of the choke by twisting it so that one gun could be used for nearly all shotgunning applications. Its effectiveness was questionable (and still is, even with the newer Poly-Choke II version). More recently, plenty of aftermarket choke companies offer screw-in choke tubes that extend beyond the muzzle. In addition to altering the bore’s choke, some contain holes that redirect escaping gasses up, thereby negating some of the forces of muzzle flip. While extended choke tubes absolutely work, they’re infrequently needed because most shotguns meant for home defense come with cylinder-bore barrels that do not need to be choked in the first place. If your shotgun is threaded for chokes, but does not have a cylinder choke tube, buy an extended one with porting.

Recoil Reducer

Muzzle brakes work by deflecting a portion of the gas that exits the muzzle and redirecting it rearward. The force of this gas pushes on the planed edges of the brake and moves the gun forward, thereby canceling out some of the forces that would otherwise push the gun rearward. In other words, it lessens felt recoil. The bigger and more aggressive the brake, generally the more recoil reduction it exhibits. However, muzzle brakes on shotguns typically do not work nearly as efficiently as those on rifles. That’s because rifles have five times the gas pressure as shotguns, and shotguns burn most of their powder in the first 12 inches of the barrel—so the rifle has a lot more gas pressure with which to work (and, therefore, to potentially reduce). Huge, square shotgun-muzzle brakes with big, flat edges like those modeled after the muzzle brakes found on Howitzers (and .50 cals.) can reduce recoil by as much as 50 percent. But, they are big, bulky and quite loud. They also direct gas to both sides of the shooter. For home defense, noise isn’t that big of an issue, but they do make the shotgun longer and less wieldy, especially around corners.

Flash Hider

As previously stated, shotguns burn most of their powder very quickly, so there is generally minimal muzzle flash in all but the shortest-barreled shotguns. However, anyone who has hunted ducks at dusk and dawn knows where the term “barking fire” originated. That said, a flash hider on a shotgun is of questionable use, at best. Whereas a rifle’s is intended to hide flash that could be used by an enemy to locate the shooter’s position at long ranges, a shotgun is a close-range weapon; when you shoot it, your enemy will know exactly where you are. So, in my opinion, “flash hiders” on shotguns fall into the just-for-show category.

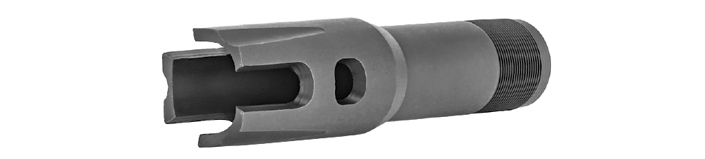

Door Breacher

For law enforcement and military personnel who specifically use a shotgun to blast down doors, a muzzle brake fitted with aggressive metal teeth is the bomb. During breaching, the shotgun’s muzzle is jammed fiercely into the door frame, wherein the teeth bite into the wood to help prevent the shotgun from losing its precise placement when the breacher turns his head to shield his eyes from the blast. This way the breacher can keep pressure on the gun barrel—to keep the muzzle in the right position on the door hinges—without the barrel slipping off its mark as the trigger is pulled. While it’s probably not needed for home defenders, if you are practiced in door breaching, a breaching tool could (in theory) be of benefit, provided you think it’s worth the extra couple inches it adds to your shotgun’s overall length.

Offensive Weapon

I was told by a Navy SEAL combat veteran that soldiers engaged in CQB often use their gun barrels as offensive weapons to give “punches” to possible assailants to keep possible threats at arm’s length. When these guys pie a room and are met with a person not holding a weapon, they can jab that person with a gun barrel rather than dropping their weapon and using a fist. This technique is much more efficient. A shotgun’s breaching tool can be used in the same way, but unlike a plain barrel, its teeth will cause some pain, thereby possibly dissuading a potential attacker from attacking—at least in theory, anyway. As for the practical applications of home defense, it’s questionable at best.

Selling Point

My hunch is that most wicked-looking, fanged, oversize muzzle devices found on factory “tactical” shotguns nowadays are designed to persuade the consumer to choose it over the run-of-the-mill, bird-hunting barrel. Why? Because it’s got the looks that kill, of course.