In the world of handguns, many people regard the old Colt Pythons as true classics. Even before Colt ceased production of these revolvers, thus turning them into collector’s items, a lot of us “old guys” considered the original blued Pythons to be the most beautiful double-action revolvers ever built. I managed to hold onto my two 1980-vintage Pythons until a couple of years ago when prevailing prices promoted the guns from “shooters” to “serious investments.”

Although I loved shooting the originals, for the last 30 years I was concerned with the revolver’s fragility when using full-power magnum loads. Still, once the two Pythons and I parted company, I wasn’t prepared for the overwhelming feeling that there was a void in my life, and I sought consolation elsewhere, primarily in the acquisition of a couple of other discontinued, but still affordable, Colts.

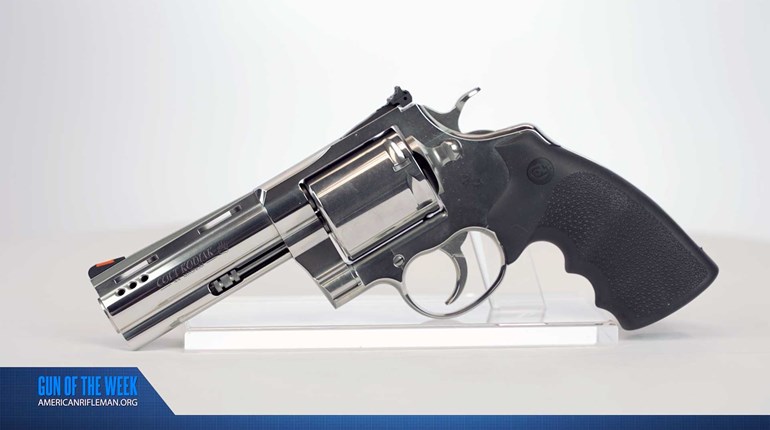

While it was not a surprise when Colt began manufacturing some of its old double-action revolvers, I had expected the Python to be the first model offered. Fortunately, it wasn’t too long until the factory announced two versions of the Python: one with a 4.25-inch barrel, the other with a 6-inch barrel. Since Shooting Illustrated focuses on the tactical/practical use of firearms, I chose to examine the shorter barrel with its history as a duty- or service-oriented handgun.

For the first showing of the new Python, Colt held a preliminary “test” event at Gunsite using some pre-production guns. In attendance were a few writers, several staff instructors and some Colt company personnel. We all signed non-disclosure agreements promising silence until Colt had a number of production guns ready for distribution. I had no problem keeping my mouth shut since my editor likes test reviews on production guns.

The event posed both risks and rewards for Colt. The risks included possible premature leaks on the new gun and some harsh comments on any potential problems that appeared before the Python went into production. The rewards included instant professional feedback from Gunsite’s world-renowned staff of instructors and hopefully enthusiastic support from the magazine writers if the session went well. For the writers, it could also provide some guidance on what to look for during future testing of production guns.

There was only one problem that surfaced at the Gunsite event, and that was an occasional soft strike that failed to ignite the primer. Every time I experienced this failure, a second strike successfully fired the gun regardless of whether I was shooting double or single action. I mention the double-/single-action element because the hammer fall distance is noticeably less when shooting double action as opposed to cocking the hammer.

A longer fall means a harder hit. Obviously, being surprised by a quiet click instead of a loud bang is an unacceptable condition on any handgun that may be used for self-defense, but it’s not too alarming when discovered on a pre-production gun. That’s why all products go through test programs. It’s also the kind of problem that’s easily fixed at the factory with an internal adjustment. And judging from the production gun I’ve been testing, it was fixed.

Externally, my 4.25-inch production test sample looked exactly like the guns fired at Gunsite. Removing the grip panels didn’t reveal any obvious changes internally, although Colt says there is 30 percent more steel compared with the original Pythons, and Colt Product Director Justin Baldini confirmed the new Python’s mainspring had been changed slightly in response to the soft-strike issues experienced at the industry event. The robust metal parts were assembled to the same basic design, and I couldn’t tell what, if any, alterations had been made to individual parts.

While re-installing the grips, I stripped the last two threads on the end of the screw that retains the grip panels on the frame. I’ll take most of the blame for this since I’m prone to using “gorilla tactics” when working on guns, and this isn’t the first time I’ve stripped the threads on a gun screw. That said, judging from the fact that slightly less than two threads had been stripped from the end of the screw, perhaps a slightly longer screw might be advisable.

Baldini said this had been shared with Altamont Grips (the company that furnishes the grips and screws to Colt). On the positive side, the grips fit the Python frame perfectly, so there was no movement or loosening of the laminated wood panels throughout subsequent shooting and handling sessions.

In my opinion, the grips looked much nicer than the clunky wood blocks on the older Pythons, plus they appear slightly smaller and slimmer. Despite that, they’re still too bulky for controlled double-action shooting by persons with short fingers or small hands. The panels extend more than a quarter-inch beyond the base of the grip frame and continue to follow the outward flare of the backstrap.

When firing heavier loads, my shooting hand slides around the right panel, and I can’t maintain my firing grip from shot to shot. No problem with .38 Spl. ammunition up through lighter .357 Mag. loads like CCI Blazer, but I was constantly struggling to regain control with heavier loads. This is not a criticism of the gun; it’s a personal fit issue that the individual shooter may need to address.

Colt has made a couple of good changes on the sights. The front ramp has a plastic orange insert, which I like on a handgun that may be needed during reduced-light conditions. The orange enhances visibility of the front blade, while the 90-degree corners still allow a precise sight picture when combined with the square notch in the rear sight. The black, adjustable rear sight (another strong preference of mine) fits nicely into a slot in the topstrap.

The sight is not rock solid like a dove-tailed fixed rear sight; it maintains its position under spring tension. If you press on it with a thumb, it will move slightly before returning to its last setting, hence the name “adjustable sight.” Additionally, the top outer edges of the rear-sight blade feature a short, 45-degree corner rather than the sharp, 90-degree corner I seem to recall on older Pythons. I carry most guns strong side in an open-top holster, and I can’t remember how many times my wrist or forearm has been gouged by pointed corners while simply moving about—not a problem with the new Python.

My test gun arrived at the same time we began the suggested/recommended/dictated quarantine caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Getting range time where one could set up a chronograph, run group tests and shoot rapid fire became difficult. The .357 Mag. packs a punch, and accuracy-testing requires serious concentration and steady hands for 100 or more rounds. Rapid fire requires a less demanding level of concentration, but greater endurance. In other words, I needed two separate range expeditions. Fortunately, Firearms Training Associates offered its outdoor range.

My shooting was done single action for both the accuracy tests and velocity measurements. There were no malfunctions (all rounds went bang) of any kind. However, the wear and tear of more than 100 rounds of carefully fired magnum loads left me with no desire to ring steel. Plus, I wanted some input from an experienced trainer with larger hands. Thankfully, Bill Murphy, owner of Firearms Training Associates, worked the steel targets firing double action. He ran the Python like they were old friends and gave it his blessing.

The situation had changed by the time I could arrange the next shooting session. Specifically, the quarantine was much more formal, and a number of gun stores and ranges had been classified as “non-essential,” (i.e. shut down). Fortunately, North County offered the needed range time and is owned by two gentlemen who had or still have original Pythons and were interested in a comparison between old and new.

Since the session would involve pounding 250 to 300 rounds of ammo through the new gun, I was eager for some trigger-time assistance from a couple of experienced Python guys. In addition, the internet had some rather hostile reviews on new production Pythons. Apparently, some shooters had experienced difficulties with light-primer strikes, damaged muzzle crowns and cylinder-rotation failures. I needed to take a close look at the Python’s performance under more tactical, less gentle circumstances.

Before the second shooting session, I cleaned my Python’s muzzle (but not the rest of the gun) and verified the crown was flawless. I doubt there’s a production factory on earth that hasn’t inadvertently released a cosmetically flawed product at some time or other. It’s an inconvenience for the consumer, but as long as the company covers the expenses of making the product right—and Colt is doing that—there’s no reason for hysteria. It happens.

Over the course of roughly 2 hours of range time, we ran about 250 rounds through the Python. Ammo included all the brands shown in the test table plus some leftover Super Vel .38 Spl. +P and some cast-bullet handloads. At one point, the Python became uncomfortably hot and was briefly set aside. The Python was not cleaned at any time during the shooting session other than a couple of muzzle wipes to check the condition of the crown. Some of the cast-bullet handloads were quite old and produced a lot of gunk that affected the trigger pull, making it slightly sticky, but still manageable.

In the course of the afternoon, there were zero malfunctions of any kind. The cylinder rotated every time the trigger was pulled. Likewise, a round fired every time the trigger was pulled. I didn’t keep an exact count, but the range owners fired about 20 to 30 rounds, a few of which were single action; the rest of the 250 rounds were fired double action.

The Internet comments had mentioned the Python’s side-plate screw coming loose, which failed to keep pressure on the hand, thus allowing it to “skip” over the cylinder ratchet causing cylinder-rotation failure. Because of that comment, I checked the side-plate screw prior to the indoor range tests, but never touched the screw at any time the gun was in my possession. There is a barely visible seam where the side plate joins the frame right where the side-plate screw enters the frame. It served as an index mark to see if the screw had moved during the firing session. The screw did not move a fraction of an inch.

A phone call to Colt revealed that the proper torque settings for installing the side-plate screws on production guns have been confirmed, and Colt is considering putting thread-locking compound on the screw threads. These will likely be hard patches rather than liquid Loctite. And again, the grip panels remained tightly in place (despite having no retention screw) and showed no play at the end of the day. I tried to manually wiggle them, but the fit was too good.

Interestingly, both owners of the Shooting Center were less than overwhelmed by the new Python compared with the older, blued versions. They acknowledged the stainless guns were more rugged than the discontinued models, but lacked the classic beauty of the 6-inch-barreled older gun. They also commented that the new gun’s trigger, while decent, wasn’t nearly as smooth as the originals. I agree with their aesthetic assessment; the old 6-inch blued Python is something special to behold.

But, while I’m emotionally moved by blued gun steel, my practical side quickly acknowledges the advantage of stainless steel, whether it’s meant for concealed carry or an outdoor adventure. The classic blued Pythons have mostly evolved into coffee table beauty queens, whereas the new stainless guns were designed for the workplace.

I also think the store owners were correct in their trigger assessment. My older Pythons had spectacular triggers that have occasionally been rivaled by the work of custom gunsmiths, but not by handguns received directly from a production line. Having said that, I think it needs to be put in context. While Colt made the new Python to look like the originals, the objective was for the new guns to survive and thrive in the kind of adverse environments that proved too harsh for the older guns. The trigger on my test gun was not spectacular, but more than up to the task.

Colt specifications dictate a trigger that will help you survive a fight, not make your shooting buddies gasp in awe when they dry-fire the Python in your living room. After having fired more than 400 rounds without being cleaned, my test gun’s trigger pull weight measured an average of 9 pounds, 6 ounces double action. I can’t address issues I didn’t experience, but my production-line Python confirmed that Colt met its objectives.