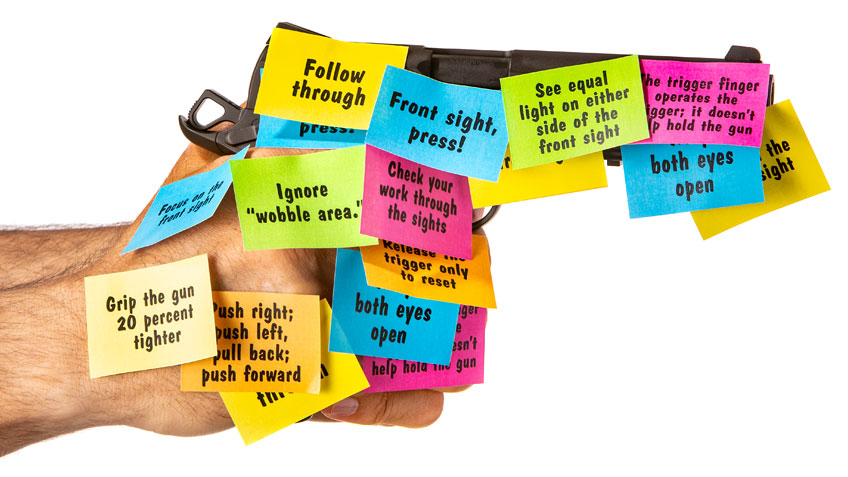

Every now and again I stumble across a little nugget of information, a handy little hint, that lies dormant in my head for some period of time before it clicks like the proverbial light bulb coming on and I can internalize it and use it to improve my pistol shooting. For instance, in a class with Todd Jarrett he kept saying “Grip the gun 20-percent tighter!”

“Twenty-percent tighter than what?” I’d wonder, before eventually realizing that grip was not only a key part of recoil control, but also fundamental to not disturbing the sight picture when shooting fast.

Another such informational nugget was acquired listening to trainer John Hearne’s “Performance Under Fire” lecture at the Paul-E-Palooza conference. He stressed the importance of “recency” in performing skills at a high level. In other words, not only did it matter how long or how often you’d been practicing a skill such as a fast draw or basic marksmanship, but also how recently the skill had been practiced. Five free-throws practiced an hour ago are a lot more useful for hoops-shooting skills than 10 last week or 100 last year.

When the importance of “recency” clicked, I got a lot more serious about knocking out a few daily dry-practice reps of my draw from concealment and made sure that every range trip included more-challenging work, like drawing to small targets or working on speed. The results at the range, even under pressure in classes with peers looking on and someone standing there with a timer, were noticeable. You’re not doing something “cold” if you did it just that morning or the night before.

From Joe Weyer at Alliance Police Training, I picked up a great analogy for recoil management. Imagine, he said, pushing a logging chain. You’re the chain, with your joints being the flexible links, and the gun is the thing that’s pushing on that chain. When the gun fires, you’re trying to efficiently transmit that recoil to the earth, so you have to stiffen the chain for a split second. As a reminder of what you’re trying to do, Weyer suggested, curl your toes as though you’re trying to grab the ground with your feet.

On the firing line, Louis Awerbuck would loudly admonish people to “Check your work through your sights!” which not only helped me internalize the idea of “follow-through,” but also probably saved my bacon in the head-to-head match at Tac-Con this year, since in that match you had to drop three falling targets in order and couldn’t go back to a previous one if you left it standing and went on to the next one.

Awerbuck’s “check your work” saying came in handy in a recent class with John Murphy of FPF Training, too. Murphy set up a reaction drill, basically telling students to start engaging a target with rapid fire and then stop as soon as they saw a laser dot appear on the target.

We were fairly close to the targets, not more than 5 yards, and I shot at a pace that let me get a good visual of the target every time my front sight settled out of recoil. As a result, I didn’t fire any shots after the red dot appeared, and the four or five shots I did fire, at .4-second splits, all went into one ragged hole. At no point was I getting beyond the boundaries of reaction time, and that saved me from making extra holes.

This gets back to the earlier point about recency, too. Since I’d been making it a point to push speed in live-fire practice sessions, as recently as just a couple days before, the .4-second splits felt extremely relaxed and slow, as though I could have paused for a sip of coffee between shots.

With a drill like that, it was readily apparent who was outrunning their headlights, and who was “checking their work through their sights” both in terms of accuracy as well as by the fact that some folks cranked off three or four shots after the red laser dot showed up on the target.

I should go back through old class notes more often and see if there are more little nuggets of knowledge that make more sense to me now.