This article, "Four Johns" appeared originally as a Fightin' Iron column in the June 2017 issue of Shooting Illustrated. To subscribe to the magazine, visit the NRA membership page here and select Shooting Illustrated as your member magazine.

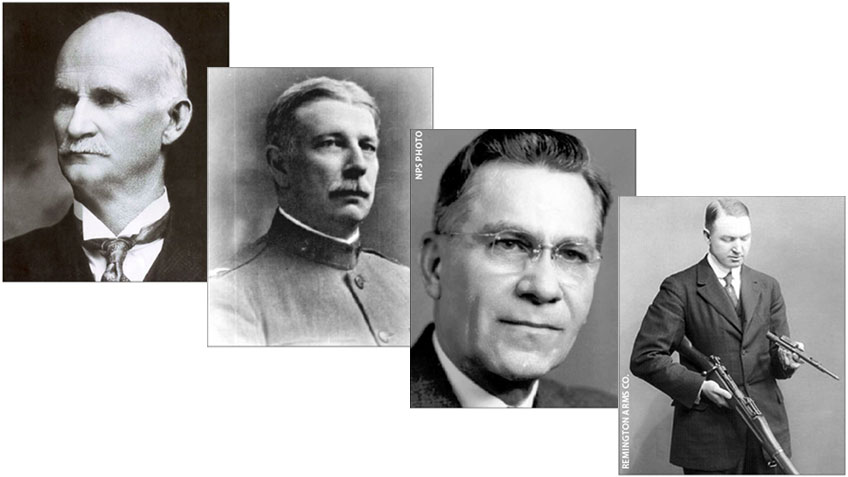

The safety of these United States has often hinged on the republic’s ability to defend itself. We’ve always had enough guys with the resolve to get it done. Happily enough, we always seem to find men who could design what was needed and apply their designs to those endless acres of Yankee steel. From bayonets to bombs, we were able to produce the blueprints that rendered fine armaments. It wasn’t all national defense, either. When there were frontiers to conquer in the time of the nation’s westward expansion, the rifle was right there with the axe and the plow. Somebody had to design and manufacture the frontiersman’s firearms. In more peaceful times, the firearm has evolved into the tool of the sportsman. We have always found men who could get it done, and by the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, there was an active and prolific arms industry in place. That was fortunate indeed as we endured a future full of conflict. That industry executed the designs of many creative engineers. Let’s look at four of the most consequential who, by sheer coincidence, all carried the given name of John.

John Moses Browning (1855 -1926) was undeniably the most successful, certainly the most prolific gun inventor ever. It is also possible that he was one of America’s shrewder businessmen. A Mormon, Browning grew up in his father’s Utah gun shop, where he was encouraged to experiment. His first rifle was a sturdy single-shot that came to the attention of Winchester. Browning engineered an agreement that permitted Winchester to manufacture a whole series of lever-action rifles and shotguns that he designed, some produced in the millions. In the late 1890s, he began to work with automatic firearms that used gas or recoil force to reload their own chamber. He even formed a relationship with Colt that led to the production of the 1911 service pistol. Some of his pistol models were made by FN America and also by Colt. In terms of sheer numbers, Browning’s best were the various models of the Browning machine gun. Made in .30 and .50 caliber, this was our major machine gun from 1917 to the present. One of the best ways to describe the scope of what he accomplished was to consider that anyone who makes any version of the Government Model pistol (Ruger, Smith & Wesson, Springfield Armory, Taurus, Remington, Dan Wesson, SIG Sauer and even Colt) is making a John Browning gun. It is easily more than 10 million guns by now.

John Taliaferro Thompson (1860-1940) was born into the U.S. Army and was educated at West Point. In those days, the brightest graduates went to the engineers or artillery. Thompson went to the artillery, but eventually ended up in ordnance. In an assignment to support the ordnance being shipped to Cuba in the Spanish-American War, Thompson came to appreciate the effect of the massed fire of early “machine guns”—in this case, Gatlings. Later, as he learned of the trench warfare in early World War I, he began to design a portable machine gun that might sweep the trenches clear of enemy soldiers with .45 ACP pistol bullets. He called it the “trench broom,” and it is better known as the Thompson Submachine Gun. Hostilities ended before the gun could be made and deployed to France. Nevertheless, a company formed to build the gun for commercial sale did well in the early 1920s. By now known as the “Tommy Gun” and beautifully made by Colt’s Firearms, the gun came to be associated with the gangster element in the U.S. Thompson was said to be somewhat remorseful about the misuse of his invention, but the gun became a staple of many units of our military in World War II and Korea. I used one a bit in Vietnam in the mid-1960s. It was a brutally effective submachine gun.

John Taliaferro Thompson (1860-1940) was born into the U.S. Army and was educated at West Point. In those days, the brightest graduates went to the engineers or artillery. Thompson went to the artillery, but eventually ended up in ordnance. In an assignment to support the ordnance being shipped to Cuba in the Spanish-American War, Thompson came to appreciate the effect of the massed fire of early “machine guns”—in this case, Gatlings. Later, as he learned of the trench warfare in early World War I, he began to design a portable machine gun that might sweep the trenches clear of enemy soldiers with .45 ACP pistol bullets. He called it the “trench broom,” and it is better known as the Thompson Submachine Gun. Hostilities ended before the gun could be made and deployed to France. Nevertheless, a company formed to build the gun for commercial sale did well in the early 1920s. By now known as the “Tommy Gun” and beautifully made by Colt’s Firearms, the gun came to be associated with the gangster element in the U.S. Thompson was said to be somewhat remorseful about the misuse of his invention, but the gun became a staple of many units of our military in World War II and Korea. I used one a bit in Vietnam in the mid-1960s. It was a brutally effective submachine gun.

John Douglas Pedersen (1881-1951) came from Danish immigrants and rose in the ranks of Remington’s engineering department. As a young designer, he even collaborated with Browning on various projects. He was the brains behind several pump-action Remingtons that were made in significant numbers. In a time when all handgun makers were building pocket autos, Remington’s was the Model 51 in .32 ACP and .380 ACP. It was a good gun—I used one for a while. Pedersen was said to have spent countless hours on the Model 51’s ergonomics. Of course, Pedersen is best known for the Pedersen Device, a gun that is utterly different. Made to quickly slip into the receiver of a lightly modified Springfield M1903 rifle, it converted the rifle into essentially a rather heavy semi-automatic carbine that took a special, short .30-caliber pistol cartridge. Issued to World War I infantrymen en-masse, this system showed great promise, but the war ended before it could be deployed. Most of the devices were destroyed, but Pedersen stayed at it, designing a new infantry-rifle cartridge and a rifle to fire it. The rifle was seriously competitive with the M1.

John Douglas Pedersen (1881-1951) came from Danish immigrants and rose in the ranks of Remington’s engineering department. As a young designer, he even collaborated with Browning on various projects. He was the brains behind several pump-action Remingtons that were made in significant numbers. In a time when all handgun makers were building pocket autos, Remington’s was the Model 51 in .32 ACP and .380 ACP. It was a good gun—I used one for a while. Pedersen was said to have spent countless hours on the Model 51’s ergonomics. Of course, Pedersen is best known for the Pedersen Device, a gun that is utterly different. Made to quickly slip into the receiver of a lightly modified Springfield M1903 rifle, it converted the rifle into essentially a rather heavy semi-automatic carbine that took a special, short .30-caliber pistol cartridge. Issued to World War I infantrymen en-masse, this system showed great promise, but the war ended before it could be deployed. Most of the devices were destroyed, but Pedersen stayed at it, designing a new infantry-rifle cartridge and a rifle to fire it. The rifle was seriously competitive with the M1.

John Cantius Garand (1888-1974) was a Canadian who came to America as a member of a family of 12 children. A naturalized citizen, he grew up toiling in the textile business, with a specialty of the complex machinery required. He took up shooting as a sport and it eventually took him to design and manufacturing work at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts. Assigned to the new service-rifle project, he came up with a basic gas-operated design that quickly grew into an immortal American firearm—the M1 rifle. It used the same .30-caliber cartridge as the famed Springfield M1903, BAR as well as the 1917 and 1919 machine guns. More than four million of these rifles were made, most of them during World War II. This was the primary infantry rifle of the U.S. armed forces during that war and the Korean conflict. No less of an authority than “ol’ Blood ’n Guts,” Gen. George S. Patton, pronounced it “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” They are still widely used, and the man who gave it his name received multiple honors from his adopted country.

John Cantius Garand (1888-1974) was a Canadian who came to America as a member of a family of 12 children. A naturalized citizen, he grew up toiling in the textile business, with a specialty of the complex machinery required. He took up shooting as a sport and it eventually took him to design and manufacturing work at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts. Assigned to the new service-rifle project, he came up with a basic gas-operated design that quickly grew into an immortal American firearm—the M1 rifle. It used the same .30-caliber cartridge as the famed Springfield M1903, BAR as well as the 1917 and 1919 machine guns. More than four million of these rifles were made, most of them during World War II. This was the primary infantry rifle of the U.S. armed forces during that war and the Korean conflict. No less of an authority than “ol’ Blood ’n Guts,” Gen. George S. Patton, pronounced it “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” They are still widely used, and the man who gave it his name received multiple honors from his adopted country.

The four Johns were all contributors to the ongoing vitality of this republic. Men as familiar with the drawing board and its instruments as they were with the Bridgeports, they were not the only ones to contribute to our safety. They have all passed on, but their designs still live. They knew their fightin’ iron.