Used by U.S. troops during the Spanish American War, the Krag-Jørgensen rifle remain a favorite among collectors.

Sometime in the mid-1880s, American ordnance officials began to face a cruel reality about the nation’s service rifle. The 1873 Springfield rifle and carbine were rugged brutes in many ways, but their ruggedness was sometimes measured by their performance as clubs or mounts for the wicked bayonets of that time. Called the “trapdoor” for the style of opening its breech, the ’73 was chambered for a powerful .45-caliber cartridge—still in use today as the .45-70 Gov’t. Both rifles and carbines had trouble extracting the early copper-cased ammo, but the cartridge was effective—although short-ranged—when it was fired. Used exclusively in the Indian Wars, the trapdoors were single-shots at a point in time when most nations were examining the possibility of repeating rifles with greater range and smaller caliber. The British, Germans and French were issuing early versions of the bolt-action rifle and most of the other nations of Europe were testing and evaluating bolt-action repeaters. That included Norway.

A Norwegian army officer named Ole Krag set about designing a new bolt-action rifle for his country and enlisted the services of an adept gunsmith named Eric Jørgensen to help. This was 1886 and the rifle they designed jointly was called the Krag-Jørgensen. Norwegian prototypes went to Denmark for service evaluation and the feedback was important in the development of the gun, which eventually became the major military rifle of both countries. It proved to be a very important arm in the ongoing history of the rifle, remaining in production in Norway all the way through World War II. Supposedly, the Germans occupying Norway ran the Norwegian plant and made Krag rifles for their own use.

Original versions of the Krag-Jørgensen rifle used an integral magazine, which pretty much surrounded the action and held 10 rounds. It was rather bulky, heavy and expensive to make. Eventually, a more-workable, five-round-variant was used. Danish Krags fired an 8x58 mm rimmed cartridge, while the Norwegian model was a 6x55 mm rimless. All of this is fairly obscure information that has no real bearing on Yankee doin’s—that is, until 1892, when we adopted the Krag.

U.S. Army Ordnance conducted extensive field trials of some 53 different service rifles at Governor’s Island, NY, in 1892. All were foreign designs from various countries: Germany, Austria, Great Britain, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark, etc. The winner was the Krag-Jørgensen and, after some contention, that rifle was adopted as our nation’s main military-service rifle. In the following decade, half a million rifles were made. It was essentially the same rifle throughout, although collectors and military-designation purists recognize 1892, 1896 and 1898 models. Further, the Krag came as a short carbine for mounted troops and a long-barreled rifle for the infantry. There are a few other variations that delight collectors—like the Cadet Rifle or the Philippine Constabulary model. While the tenure of the Krag-Jørgensen rifle in service was only about 11 years, it was a well-regarded arm by the Soldiers, Sailors and Marines who used it. Replaced beginning in 1903 by the legendary ’03 Springfield, the Krag was used in a wide variety of different roles—including one rather benign one we’ll get to in a moment.

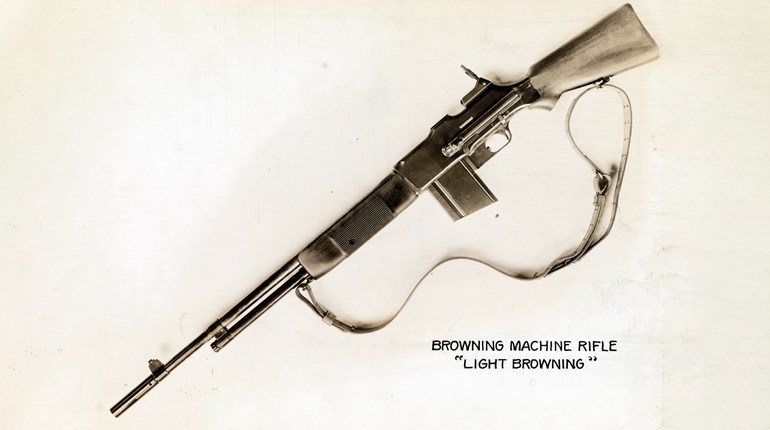

The U.S.-made (Springfield Armory) Krag-Jørgensen rifle was chambered for the .30-40 Krag cartridge, an early smokeless-powder round that delivered a 220-grain bullet at about 2,000 fps. For that period, it was effective performance. Carbine barrels were appropriately short for the job at about 22 inches. The more-common rifle had a barrel a full 30 inches in length. While this seems an unnecessarily long barrel, such was the style for infantry rifles of the turn-of-the-20th-century era. Consider what happens when you mount a 16-inch bayonet to a 30-inch barrel—you are now fighting roughly 4 feet away. In those days, bayonets were not a device you fitted to your rifle when you were out of ammunition. Infantry troops practiced with their bayonet for hours.

The major distinguishing feature of the U.S. Krag was the action, particularly the unique box magazine on the right side of the receiver. A typical four-step turnbolt (lift, pull, push, lower), the Krag-Jørgensen rifle was renowned for the smoothness of the stroke. It was because the lugs that lock the bolt closed are located at the rear, where the operator has more leverage. Lugs at the front of the bolt are much stronger, but the strength of the Krag’s action was deemed sufficient when examined by ordnance experts.

Holding five rounds of .30-40 Krag ammo, the box magazine was made of a machined-steel forging. It was hinged along the right bottom edge and pivoted open, down and to the right. Riflemen reloaded by dropping five rounds into the opened box. The magazine’s inner surfaces were shaped in such a way that closing the box caused them to align perfectly. The action also featured a magazine cut-off—a small lever that could be turned to block feeding from the magazine. An infantryman shooting with a full magazine and the cut-off “on” could fire single shots and reserve his loaded magazine for close-in use.

The Krag-Jørgensen rifle was a long way from being perfect, but it served us well in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine War and a few other lesser imbroglios. Many Krags were sporterized into some mighty graceful deer rifles, as the performance of the .30-40 Krag cartridge fell somewhere between the .30-30 Win. and the .30-’06 Sprg. When I went to find a sample Krag to refresh my recollection of the rifle, I ended up fondling just such a sporter, complete with a custom stock for use with iron sights. Glancing at the action, I recalled just how the thing worked.

When I was a gunstruck teen, I belonged to a youth organization called the Boy’s Brigade. Sponsored by my local church, this was a national body, with many of the same roots as the Boy Scouts of America. The Boy’s Brigade was a more military-oriented group than the scouts, but now long gone and forgotten. Military suggests weaponry and, down at the end of the church gymnasium, there was a long, covered rack of military-surplus rifles. I well remember the Thursday-night drills of my teenage years, when I learned the manual-of-arms with a firing pin-less Krag-Jørgensen rifle, a fine hunk of fightin’ iron.