The Problem

You’re a firearms instructor for a Mid-Atlantic sheriff’s department and you also teach NRA courses for concealed-carry certification.

Recently your department transitioned from the Beretta 92 to the Glock G22. Most of your department’s deputies qualified well, although some shot high on the silhouette target you use for qualification.

One deputy, however, failed to qualify on multiple tries and no matter what you tried, his shots always grouped at the bottom or below the target. You and an assistant instructor shot the deputy’s pistol to verify its zero.

Previously, the deputy in question has always succeeded to qualify with the Beretta, but now he’s become discouraged with your new service pistol and is contemplating early retirement due to his inability to qualify. He’s a good man and you don’t want to lose him because of something like this. You’re desperately seeking a way to help him improve his shooting and qualify with the new pistol.

The Solution

There are a variety of reasons why your deputy is finding it difficult to qualify with the new pistol. Assuming it isn’t possible to “grandfather” him with his Beretta 92 with which he has qualified in the past, there are a few helpful things that you can try.

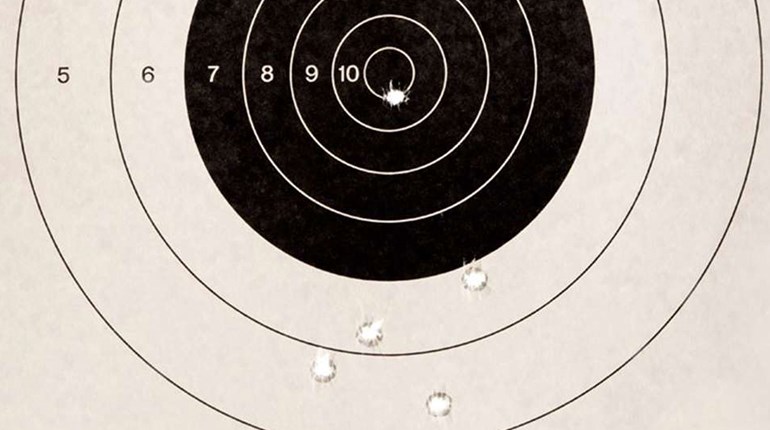

Usually the problem comes from one or more issues involving the subconscious mind and/or visual conditions due to changing eyesight or the lack of understanding of what the eyes really need to see in order to deliver a good shot. A general rule to go by that can help to narrow the field is what kind of a group can the shooter muster regardless of its placement on the target.

If there is no discernable group, the problem, more often than not, pertains to the brain—not the eyes. This seems to be apparent based on the description of the deputy’s performance.

When going to a more-powerful pistol, such as your agency is doing, recoil of the pistol increases and noise often increases as well. From a mental standpoint, this puts the shooter outside of their comfort zone. It’s not what they are used to and subsequently causes them to fight the gun to keep it under control, resulting in involuntary movement of the gun at the anticipated instant of discharge, which pushes the gun forward to counteract the recoil. This results in hits placed low or below the target.

A good diagnostic for this is to use the old ball-and-dummy drill to determine if the shooter adds movement to the gun as the trigger is pulled. This drill can be done several ways, but intermixing dummy rounds in the shooter’s magazine of live ammunition is an easy way to prove to the shooter what is taking place when the trigger is pulled.

If the muzzle dips appreciably when the trigger is pulled on a dummy round, the shooter is uncomfortable with recoil and sound of the pistol, and has unconsciously developed a flinch. This is a natural response for armed professional and responsible citizen alike, which can be overcome by two simple inoculation drills.

Simply take the shooter to a safe area at your range with just a backstop and no target. Under your close supervision, have them point their loaded pistol into the backstop, close their eyes and fire one shot at a time on your command, allowing them to concentrate on the sound of the gun when they pull the trigger. Subtle suggestions during firing to, “listen to the pop of the gun as you pull the trigger” will help to attenuate the negative emotion created by the sound of the firearm discharging. Let the shooter continue for several shots, one at a time, until they are comfortable with the noise. Let them tell you when they are comfortable, as it is different with each individual. Usually less than a magazine affects the cure.

Once this is complete, the second inoculation drill to undertake is to eliminate concerns about gun movement during discharge. While at the safe but empty backstop, have the student load the gun and fire only on your command—one shot at a time—looking specifically at the side of the gun at first , then from the back of the gun to determine how little it moves at the moment of discharge. Soft suggestions to the shooter of, “feel the push of the gun against your hands as the muzzle lifts and settles each time the trigger is pulled” tend to make the gun’s movement more palatable during each discharge.

Avoid using words like “kick” and, to a lesser degree, “recoil” when referencing gun movement during firing. (Think about it: Do you like being kicked? Shooters don’t, either.) Again, less than a magazine of ammunition is usually all it takes, but let the shooter make the determination as to when they are comfortable with the noise and movement of the gun when discharge takes place.

These two drills should be reinforced periodically for any shooter who has added movement to a gun when they pull the trigger on live or dummy ammunition when they think there is a live round in the chamber. Hopefully, my suggestions will extend your deputy’s career a few more years.